22 Jul 2025

Paraprostatic cyst presentation: case study in German shepherd

Austin Shipway BVSc, MRCVS and Shaun Calleja BVetMed, DipACVIM, MRCVS discuss what can be done to confirm the important diagnosis of this, often asymptomatic, issue.

Image: Dyrefotografi.dk/ Adobe Stock

Prostatic cysts are an uncommon presentation in dogs, although risk appears to be higher in larger dogs and some breeds, including the German shepherd dog1,2. Cystic changes can be seen alongside prostatic conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), prostatitis and prostatic abscesses in entire male dogs.

Small, uncomplicated prostatic cysts are often of little clinical importance, as most patients are asymptomatic; however, they are known to cause disease when they grow large enough to compress and displace adjacent structures, including the urinary tract and the colon, or they become infected. Perineal hernias may also be present in affected dogs.

We were presented with a four-year-old German shepherd dog with non-specific signs of tenesmus and constipation, an abdominal mass being identified on palpation. Investigations, including diagnostic imaging, fine needle aspiration and cytology, and tissue biopsy for histopathology, confirmed an extraparenchymal prostatic cyst. These work-ups prior to surgery can help identify the extent and origin of the abdominal mass, the presence of infection, haemorrhage and communication with the urinary tract. Surgical resection of the lesion with omentalisation and orchidectomy was successful, with no recurrence of clinical signs.

Case: German shepherd

A four-year-old, entire male German shepherd dog initially presented with a five-day history of constipation, tenesmus, flattened faeces and polydipsia. On abdominal radiography (Figure 1), a large structure was identified in the caudal abdomen adjacent to the bladder. Aspiration yielded purulent fluid, with cytology revealing marked neutrophilic inflammation; micro-organisms were not identified. Treatment with marbofloxacin (Marbocyl P, 80mg once daily PO; Vetoquinol) and clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin (Synuclav, 500mg twice daily PO; MiPet) was associated with reduction in mass size and improved faecal shape. Signs recurred after completion of the antibiotic course, along with diarrhoea and fever/hyperthermia, at which point the dog was referred to Lumbry Park Veterinary Specialists.

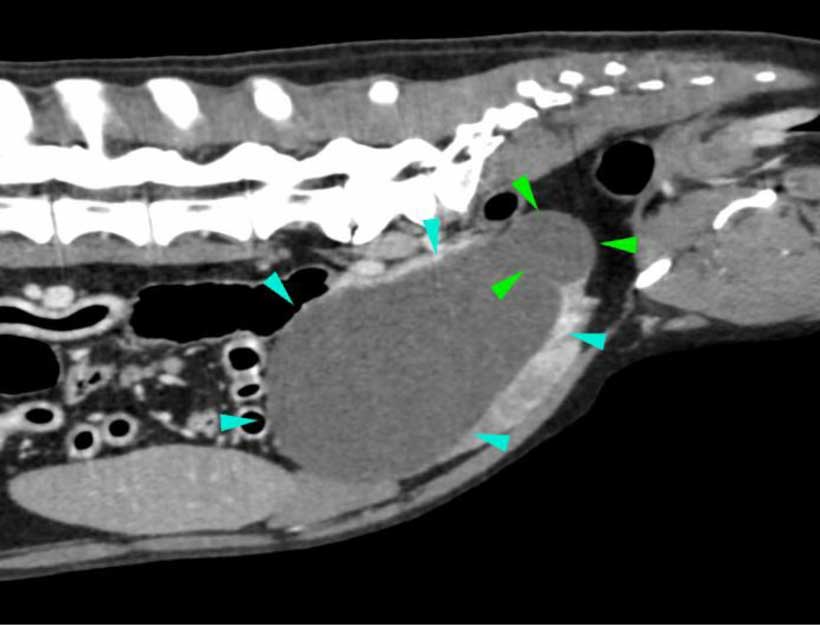

Computed tomography of the abdomen showed a large, homogeneous, fluid-filled cavity expanding from the right lobe of the prostate and a smaller cavity on the caudo-dorsal aspect of the prostate (Figure 2), with appearance suggestive of a prostatic abscess or cyst. The prostatic urethra, bladder and descending colon were displaced due to mass effect from the large, cystic structure. Urinary tract infection was also suspected based on hyper-attenuating urine, with ureteric vein dilation and ill-defined soft tissue surrounding the left distal ureter raising concerns of ureteritis and possibly pyelonephritis.

Ultrasound-guided aspiration of the fluid-filled lesion yielded approximately 500ml of turbid yellow fluid. Fluid analysis showed a poorly cellular serous fluid with minimal neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation. Urine and cystic fluid cultures were negative.

Pradofloxacin (Veraflox, Elanco, 120mg once daily PO) was administered in anticipation of surgery while the culture results were pending.

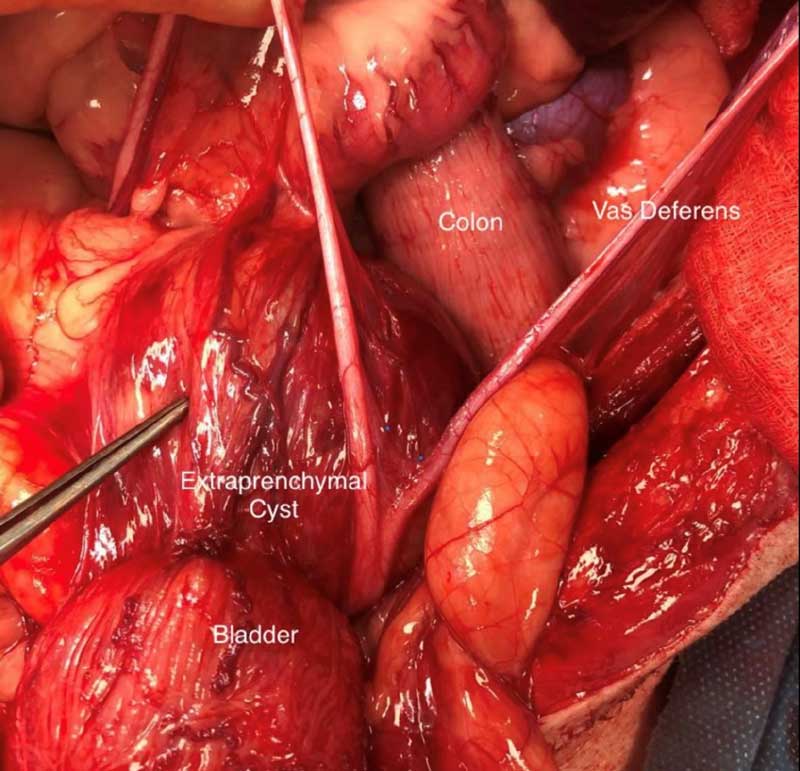

Anaesthesia was induced and maintained routinely. Preoperatively, an epidural local anaesthetic block was performed using bupivacaine (Marcain Steripack 0.5%; Astrazeneca) and morphine (Morphine Sulfate Preservative Free 10mg/ml). Pre-scrotal open orchidectomy was first performed, followed by midline celiotomy for resection of the prostatic cyst. Abdominal inspection located the extraparenchymal cyst just cranial to the prostate (Figure 3), with complete examination of the abdomen revealing no further abnormalities.

The cystic lesion measured approximately 15cm in diameter and was filled with clear, yellow fluid. Blunt dissection was used to separate the right ureter from the ventral aspect of the bladder and the vasa deferentia from the cyst. The cyst was then partially resected. Urine leakage into the cyst was noted, with a communication identified between the cyst and the caudal bladder/trigone region. The leakage site was closed using 2.0 metric polydioxanone and omentalised. The cyst was also omentalised. An in-dwelling urinary catheter was placed postoperatively.

Postoperative analgesia included methadone (Comfortan 10mg/ml; Dechra), paracetamol (injectable and oral), and gabapentin. Trazodone was also administered to alleviate anxiety. Antibiosis using pradofloxacin as previously prescribed was continued for a further 10 days postoperatively. IV fluid therapy using lactated Ringer’s solution was given as clinically indicated.

Recovery was smooth, with no postoperative complications. The urinary catheter was removed after two days, and the patient was discharged three days after the procedure.

At follow-up seven weeks later, no ongoing clinical signs were reported. Repeat urinary tract ultrasound revealed a 2.5cm intraparenchymal prostatic cyst; the prostate was otherwise normal in size and appearance.

Histopathology of the cyst wall confirmed a paraprostatic (extraparenchymal) cyst, with inflammation surrounding the cyst. There was also benign prostatic hyperplasia and evidence of chronic prostatitis. There was no evidence of neoplasia. The testes were histologically normal. Culture of submitted cyst tissue was negative.

Extraparenchymal prostatic cysts

Clinical signs of prostatic disease include stranguria, pigmenturia, urinary incontinence, tenesmus, constipation and flattened stools, with signs of dyschezia being more suggestive of significant prostatomegaly. Perineal hernias may also be identified concurrently. Many animals are asymptomatic, with prostatic disease being identified incidentally3,4,5.

Prostatic cysts are categorised into two types: intraparenchymal and extraparenchymal. Their aetiology remains unclear. Intraparenchymal cysts (also known as intraprostatic or retention cysts) develop within the parenchyma of the prostate capsule and can form solitary or multiple lesions. They are thought to form due to obstruction of the prostatic ducts by benign prostatic hyperplasia, impairing the drainage of prostatic fluid and causing secretory stasis. Extraparenchymal cysts (also known as paraprostatic cysts) are not closely associated with glandular tissue. They tend to form separately to the prostate and, unlike intraparenchymal cysts, usually do not communicate with the urethra. Extraparenchymal cysts are thought to develop from the uterus masculinus, a remnant of the Muellerian duct system in male dogs4, 6-9.

On radiography, prostatic cysts may appear as a caudal abdominal mass, which can represent a wide array of differentials. It is important to note that extraparenchymal cysts should not be confused with the bladder as they can appear similar10. Mineralisation of the cyst wall can help differentiate the lesion from the bladder and often aids the diagnosis of a prostatic cyst5,11. Nevertheless, mineralisation should not be solely relied on and a contrast urethrocystogram may help differentiate the prostate, bladder and other affected structures7,11. Contrast radiographs may also identify a communication between the urethra and the prostate or lesion7.

Ultrasonography allows the fluid-filled cyst to be visualised, typically as a thin-walled structure filled with anechoic fluid with varying degrees of mineralisation and acoustic shadowing10,11.

CT helps to confirm the position of the cyst, as well as accurately determining prostatic size, shape and health based on the density of the tissue. CT combined with ultrasonography is often considered the best imaging tool to achieve a diagnosis, guide surgical planning and rule out other potential causes of clinical signs10, 12.

Additional testing including aspiration of fluid, urine and prostatic tissue can help support a diagnosis and rule out complications such as infection – cysts and abscesses are known to coexist and nearly half of prostatic cysts contain bacteria5,13. Measurement of cystic fluid creatinine concentration can help identify communication with the urinary tract, with fluid:serum creatinine ratio greater than 2:1 consistent with the presence of urine14.

Surgical debridement is the treatment of choice for prostatic cysts, with omentalisation also recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence5,9,15.

Ultrasound-guided drainage helps relieve clinical signs while awaiting surgery and, in some cases, may even provide resolution4,14. Orchidectomy is also recommended as part of treatment for prostatic cysts (as well as many other prostatic diseases); it helps reverse prostatic cystic change through involution of glandular hyperplasia and reduces prostatic fluid secretion. Prostate size typically decreases by 50% three weeks after castration5.

Surgical resection of prostatic cysts is typically associated with a very good long-term prognosis, with remission of clinical signs reported in 88.6% of dogs in one study15. Recurrence also appears to be uncommon, with a recurrence rate of 4.5% reported in the same study. Meticulously breaking down and removing all the septa and omentalising all regions of the cyst may help reduce the risk of recurrence, as may castration15.

Conclusion

Prostatic cysts are often asymptomatic, but once clinical signs develop, thorough examination, combined imaging modalities and sampling can help confirm a diagnosis. Surgical resection and omentalisation, castration and treatment of secondary problems are the treatments of choice and are associated with a good long-term prognosis. An understanding of the potential underlying aetiology and structure of the cysts, and their implications for surgery, may help reduce the risk of perioperative complications and recurrence.

- This article appeared in Vet Times 2025 (Volume 55, Issue 29, Pages 14-16)

- Check out this similar article from our clinical archive

Authors

- Austin Shipway qualified at the University of Bristol in 2021. He joined Lumbry Park Veterinary Specialists in 2023 and had just completed his rotating internship at the hospital.

- Shaun Calleja is an ACVIM board-certified clinician in small animal internal medicine. He joined the medicine team at Lumbry Park Veterinary Specialists in 2021 after completing his small animal internal medicine residency.

References

- 1. Polisca A, Troisi A, Fontaine E, Menchetti L and Fontbonne A (2016). A retrospective study of canine prostatic diseases from 2002 to 2009 at the Alfort Veterinary College in France, Theriogenology 85(5): 835-840.

- 2. Black GM, Ling GV, Nyland TG, Baker T (1998). Prevalence of prostatic cysts in adult, large-breed dogs, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 34(2): 177-180.

- 3. Preda (Constantinescu)V, RoscaCodreanu MI, Cristian AM and Codreanu M (2022). Clinical-diagnostic coordinates in prostatic and paraprostatic cysts in dogs, Scientific Works Series C Veterinary Medicine LXVIII(1): 120-124.

- 4. Johnston SA and TobiasKM (2018). Veterinary surgery: small animal (2nd edn), Elsevier, St Louis: XXII(2,379): 1-86.

- 5. Freitag T, Jerram RM, Walker AM, Warman CG (2007). Surgical management of common canine prostatic conditions, Compend Contin Educ Vet 29(11): 656-658, 660, 662-663 passim; quiz 673.

- 6. Kyllar M and Cizek P (2020). An unusual case of infected uterus masculinus in a dog, BMC Vet Res 16(1): 194.

- 7. Head LL and Francis DA (2002). Mineralized paraprostatic cyst as a potential contributing factor in the development of perineal hernias in a dog, J Am Vet Med Assoc 221(4): 533–535.

- 8. Tura G, Ballotta G, Cunto M, Orioles M, Sarli G and Zambelli D (2023). Clinical and histological findings of male uterus (uterus masculinus) in three dogs (2014–2018), Animals 13(4): 710.

- 9. White RAS, Herrtage ME and Dennis R (1987). The diagnosis and management of paraprostatic and prostatic retention cysts in the dog, J Small Anim Pract 28(7): 551–574.

- 10. Ragetly GR, Bennett RA, Chow EP and Naughton JF (2009). What is your diagnosis? Discrete prostatic cysts, J Am Vet Med Assoc 234(9): 1,127–1128.

- 11. Renfrew H, Barrett EL, Bradley KJ and Barr FJ (2008). Radiographic and ultrasonographic features of canine paraprostatic cysts, Vet Radiol Ultrasound 49(5): 444-448.

- 12. Kuhnt NSM, Harder LK, NolteI and Wefstaedt P (2017). Computed tomography: a beneficial diagnostic tool for the evaluation of the canine prostate? BMC Vet Res 13(1): 123.

- 13. LévyX, NiżańskiW, vonHeimendahlA and MimouniP (2014). Diagnosis of common prostatic conditions in dogs: an update, Reprod Domest Anim 49(s2): 50–57.

- 14. Bokemeyer J, Peppler C, Thiel C, Failing K, Kramer M and Gerwing M (2011). Prostatic cavitary lesions containing urine in dogs, J Small Anim Pract 52(3): 132-138.

- 15. DelMagno S, Pisani G, Dondi F, Cinti F, Morello E, Martano M et al (2021). Surgical treatment and outcome of sterile prostatic cysts in dogs, Vet Surg 50(5): 1,009-1,016.