16 Dec 2025

Ear cytology – a guide on what to do, what for and when

Karina Fresneda DVM, DipIACVP explains how this technique can help accurately diagnose otitis externa in cats and dogs.

Image: Ryan / Adobe Stock

Otitis externa remains one of the most frequent reasons for veterinary consultation in small animal practice, with a reported prevalence in dogs of 7.3% in primary care1.

While otitis externa can occur in cats, it is not as common as in the canine population2. In both canine and feline patients, early, accurate diagnosis and treatment is essential to prevent otitis becoming chronic or recurrent. Once established, chronic otitis can lead to fibrosis, stenosis and mineralisation of the ear canal, resulting in irreversible change.

By definition, otitis externa refers to inflammation of the epithelium lining the external ear canal, which may or may not be associated with infection3.

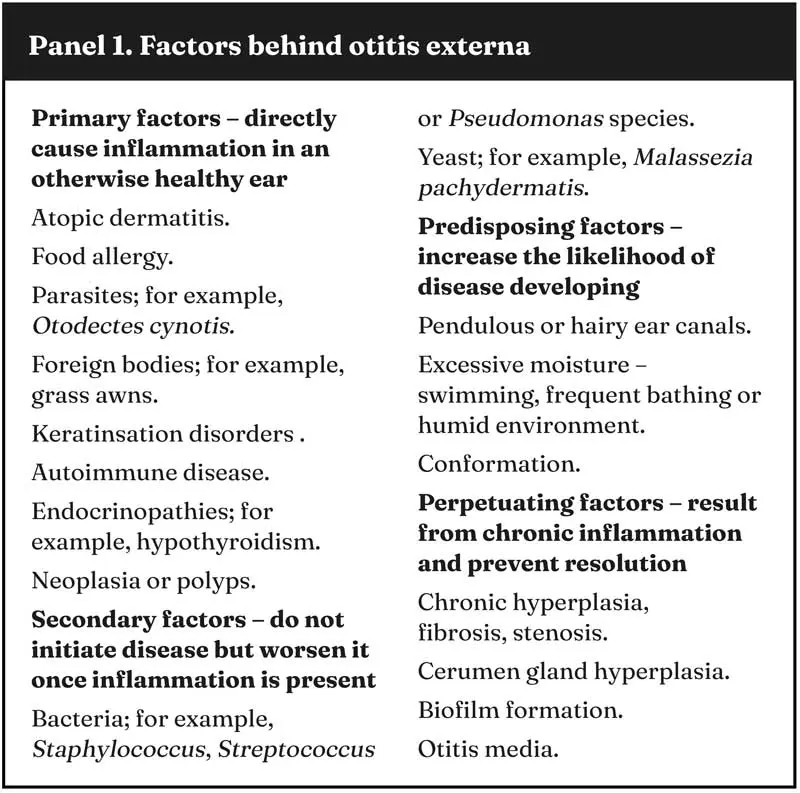

The condition is typically multifactorial, often arising from a combination of primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors (Panel 1)4. Its management, therefore, requires both accurate diagnosis of infection and identification of the underlying causes that allow inflammation to persist.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of otitis externa varies considerably depending on the underlying cause and stage of disease.

In mild or early cases, owners may simply report occasional head shaking or scratching. As inflammation progresses, the ear often becomes more painful, and changes to the pinna and canal will be visible. A full diagnostic workup begins with a detailed history and visual examination of the pinnae, followed by palpation of the canal and otoscopic inspection. Assessment should include both ears, even when disease appears unilateral.

A clinically normal ear canal is smooth, pale pink and free of discharge. When otitis is present, clinical signs may include erythema, alopecia of the pinna, excoriations secondary to self trauma, hyperpigmentation, crusting and, in some cases, ulceration of the ear canal.

Canine otitis externa: reviewing available management options

Chronic inflammation leads to pathological changes including glandular hyperplasia, glandular dilation, epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis5. These changes progressively narrow the ear canal, impair ventilation and trap moisture, creating a self-perpetuating environment for further microbial growth.

In chronic or recurrent cases, fibrosis and mineralisation may lead to partial or complete stenosis, making topical therapy less effective and otoscopic examination difficult. Without appropriate management, this process culminates in irreversible end-stage ear disease.

Otitis may be unilateral or bilateral. Acute onset unilateral disease should prompt investigation for a foreign body, whereas a slower onset may be more indicative of polyps or neoplasia. In contrast, bilateral disease is more often secondary to underlying food allergy, atopy or other systemic conditions, including endocrinopathies.

However, due to the multifactorial nature of otitis externa, diagnosis cannot rely on clinical signs alone and cytology is an essential part of the initial workup.

Role of cytology

Cytology is a simple, quick and invaluable tool in the diagnosis and management of otitis externa. It confirms whether infection is present, helps identify the microorganisms involved and provides an objective assessment of inflammation.

In an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, cytology provides an immediate, evidence-based method of ruling in or out microbial infection, preventing empirical treatment based solely on clinical signs. While culture and sensitivity is indicated in some cases, it can be poorly predictive of the response to topical treatment.

Cytology should ideally be carried out at first presentation and, where infection is identified, repeated until full resolution has been achieved. Topical therapy should only be stopped when cytology shows no bacteria or yeast, and no inflammatory infiltrate6. Some authors recommend weekly rechecks to help determine when this point has been reached7.

In most cases, cytology can be performed in house using a good quality light microscope and easily incorporated into existing workflows. Alternatively, samples may be sent to an external diagnostic laboratory – especially when further testing is anticipated.

Sample collection and preparation

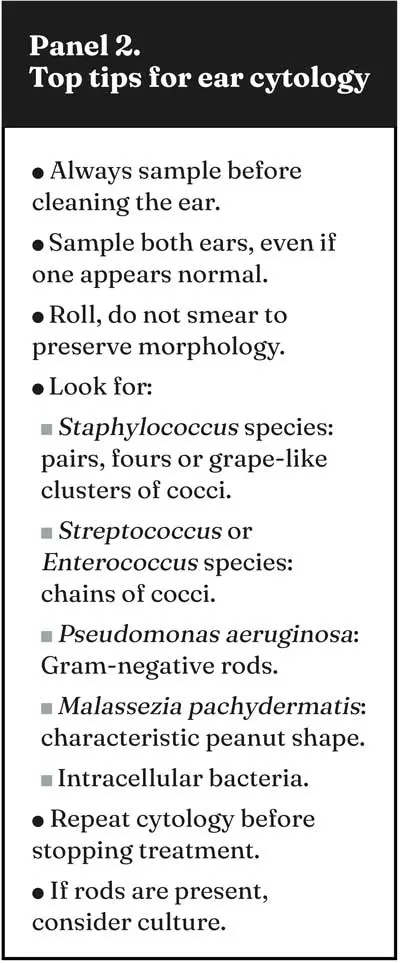

Accurate cytology begins with an appropriate sampling technique (Panel 2). After otoscopic examination of the ear canal, debris and exudate are collected using a sterile swab. The swab should be inserted to the level where the vertical canal turns into the horizontal canal and rotated gently to collect material.

Sampling both ears is recommended, even when only one appears clinically affected.

If cytology and culture are both required, the swab should first be rolled along one or two clean glass slides before being placed into a transport medium. Rolling, rather than smearing, helps preserve cell morphology. In painful ears, sedation and appropriate analgesia allow thorough assessment and easier sample collection, minimising the risk of trauma to the ear canal or tympanic membrane.

Slides should be air dried before staining. If ectoparasites are suspected, an unstained preparation can be examined under low power (4× to 10× objective) in mineral oil to look for Otodectes cynotis in dogs and cats, or Psoroptes cuniculi in rabbits. Demodex species mites may also be identified using a firm swabbing technique or superficial scraping of the pinna.

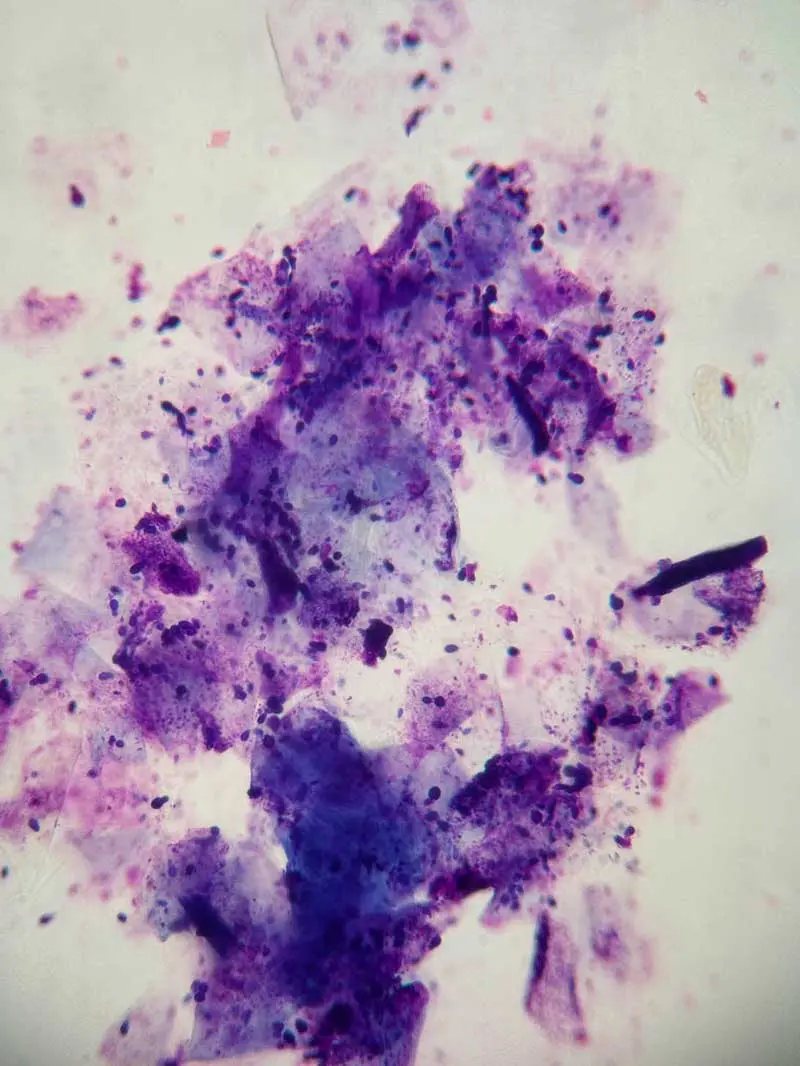

Staining is typically performed using a Romanowsky-type stain or a modified Wright’s stain. Once stained and dried, slides should be examined systematically. Examination under low power provides an overview of background material, inflammation and cellularity, while focusing on areas of interest with higher magnification (40× and 100× oil immersion) allows assessment of bacterial morphology and numbers (Figure 1).

Cytological findings

Bacteria

Bacteria are common in both acute and chronic otitis. Cocci are usually Gram-positive and, most often, Staphylococcus species. These typically appear in pairs, groups of four or irregular grape-like clusters.

Streptococcus and Enterococcus species can also be involved in the pathogenesis of otitis externa, and they typically form pairs that link up into chains.

Bacilli (rods) are of particular concern – especially when accompanied by degenerate neutrophils or purulent debris. This is because in dogs, Gram-negative rods are most frequently Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen usually associated with painful, chronic otitis that is challenging to treat.

Corynebacterium species may also be present and can look very similar to Pseudomonas on Romanowsky-type stained slides. When rods are seen, or when cocci and rods are mixed, culture can be useful to guide therapy.

Yeast

Malassezia pachydermatis remains the most common yeast identified in otitis externa. The organisms are larger than bacteria and stain dark blue-purple with a characteristic peanut or footprint shape. A small number may be present in normal ears; one study suggests around three to four yeasts per high-power field is typical in healthy canals8.

Higher numbers, clustering, or association with inflammation or keratin debris suggests clinical significance. Heavy Malassezia species overgrowth is commonly pruritic, producing brown, waxy discharge with a distinctive odour.

Inflammatory cells

The presence of inflammatory cells adds important context. Occasional neutrophils can occur in allergic or irritant otitis, but large numbers – particularly degenerate neutrophils containing intracellular bacteria – are indicative of infection.

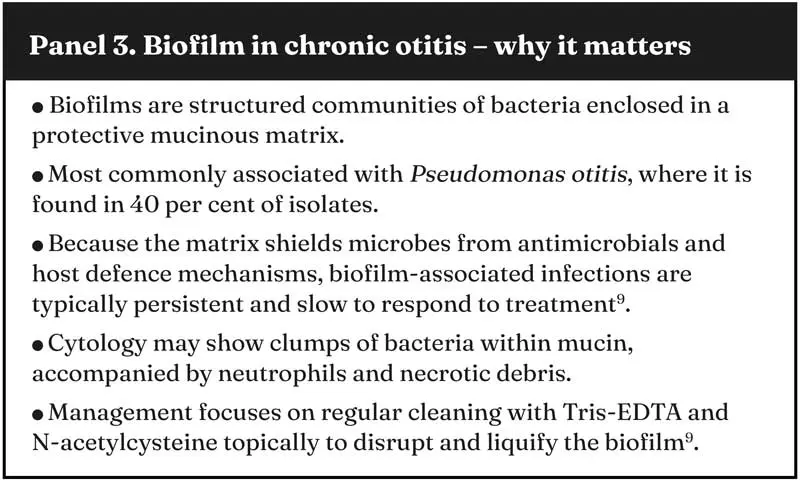

The presence of red blood cells may indicate ulceration or self trauma, while mucus and clumps of neutrophils and bacteria may suggest early biofilm formation (Panel 3) – especially in chronic Pseudomonas species infections. Taken together, these findings help determine the dominant disease pattern. In erythroceruminous otitis, large numbers of Staphylococcus species or Malassezia pachydermatis are typical, usually with minimal neutrophilic inflammation. Conversely, suppurative otitis is generally associated with Gram-negative rods and heavy neutrophilic infiltrate3.

When to culture

While cytology remains the preferred first-line laboratory diagnostic tool, cases exist where culture and sensitivity testing is needed. This includes chronic or recurrent cases, or when systemic antibiotics are needed in cases of otitis media.

Culture results should always be interpreted alongside cytology. Culture alone provides no information on bacterial load, inflammatory response or whether the sample reflects the microbial population deep within the canal.

Cytology not only confirms whether organisms are present in significant numbers, but in cases of mixed culture results, it also helps determine which bacteria are clinically relevant; for example, identifying intracellular bacteria within degenerate neutrophils provides a much stronger indication of pathogenicity and the need for targeted antibiotic therapy.

Other diagnostics

Most cases of otitis externa can be managed successfully with cytology, thorough cleaning and appropriate topical therapy. However, when otitis media is suspected, such as when the tympanic membrane cannot be visualised, the ear remains painful despite treatment, discharge rapidly recurs, or neurological signs are present, further investigation is required. Advanced imaging, including CT or radiography, can help assess bony change, the presence of fluid within the tympanic bulla and whether surgical intervention may be necessary.

Conclusion

Ear cytology remains one of the most valuable diagnostic tools available to the small animal clinician.

It should always be guided by clinical context, but can help confirm whether infection is present, identify pathogens, help select appropriate topical therapy and provide a clear endpoint for treatment.

Incorporating cytology into every ear consultation not only supports responsible antimicrobial use, but also improves case outcomes, reduces recurrence and spares patients from the discomfort and long-term consequences of chronic ear disease.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 50, Pages 6-8.

Author

Karina Fresneda graduated from the National University of the Centre of Buenos Aires Province in Argentina in 2000, and after two years of training, she became a specialist in anatomo-histopathological veterinary diagnosis. She has been teaching in infectious diseases at the same university for 15 years. At the same time, Karina was gaining experience in her clinic and laboratory, as a clinician and working in clinical pathology, cytology and histopathology. She took a three-year residency in anatomic veterinary pathology at the University of California, Davis, where she received intensive training in this field. Karina also enjoys teaching different courses on clinical pathology, cytology and histopathology.

Canine otitis externa: reviewing available management options

References

- 1. O’Neill DG et al (2021). Frequency and predisposing factors for canine otitis externa in the UK - a primary veterinary care epidemiological view, Canine Med Genet 8(7): 7.

- 2. Ordeix L (2016). Otitis externa in cats: differentials and diagnosis, WSAVA Congress Proceedings, WSAVA, Cartagena.

- 3. Nuttall T (2023). Managing recurrent otitis externa in dogs: what have we learned and what can we do better?, J Am Vet Med Assoc 261(S1): S10-S22.

- 4. Miller WH et al (2013). Diseases of eyelids, claws, anal sacs and ears. In Miller WH et al (eds), Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology (7th edn), Elsevier, St Louis: 714-773.

- 5. Bajwa J (2019). Canine otitis externa – Treatment and complications, Can Vet J 60(1): 97-99.

- 6. Paterson S (2020). Ear cytology for the veterinary nurse, UK-Vet Companion Animal, tinyurl.com/2zahk75v

- 7. Papajeski B (2020). Ear cytology: sampling, processing, and microscopic evaluation, TVN, tinyurl.com/3ya3j72y

- 8. Shaw S (2016). Pathogens in otitis externa: diagnostic techniques to identify secondary causes of ear disease, In Pract 38(Suppl 2): 12-16.

- 9. Hensel P and Hensel N (2021). Treating otitis externa in dogs, TVP, tinyurl.com/3z37hswv