6 Jan 2026

Tendon injuries: diagnostics, treatment and management

Mélanie Perrier MRCVS discusses recent updates on this issue, offering options and choices for professionals.

Image: Annabell Gsödl / Adobe Stock

Tendon and ligament injuries are an important cause of lameness in the horse, and can be associated with reduced performance, increased recovery time and associated cost of treatment, and a high risk of re-injury in some instances.

While ultrasonography remains the first line of diagnostic options for tendon and ligament injuries, other modalities have become available over the past few years to try to refine and improve our diagnostic capacity.

Among those, some advanced techniques using ultrasound and especially the use of Doppler have been described together with contrast radiography. Regarding more advanced imaging modalities, besides MRI, which has been historically one of the gold standards for diagnosing soft tissue lesions, the wider availability of standing CT over the past year or so has seen its increased use in diagnosing tendon and ligament injuries. Finally, positron emission tomography (PET) has also become more widely available.

This article will review updates on recent diagnostic options that have been available over the past few years, together with current evidence on treatment choices and management.

More on this equine topic

Good physical exam: what we can learn from palpation and flexion

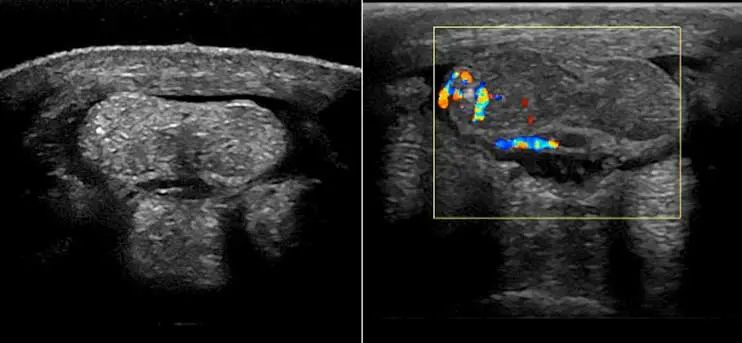

Contrast radiographs

While radiographs are not commonly used to diagnose soft tissue pathology, the use of contrast radiographs may be helpful – especially to diagnose pathology within the digital flexor tendon sheath. One publication identified that contrast tenography was sensitive for manica flexoria tear and specific for deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) tears, with a lower sensitivity and specificity for palmar/plantar annular ligament pathologies. Tenography remains an economic and easy modality that should not be overlooked, as it can be extremely useful to diagnose certain tendinous pathologies1 (Figure 1).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound remains one of the most widely used imaging modalities in equine practice. While greyscale ultrasound has been used and is still being used extensively for diagnosis tendon and ligament injury, it is limited to give structural information only, which is subjective, underestimates true lesional size, has no predictive ability and offers limited information on function. Therefore, it should be interpreted with caution.

A recent publication identified improved diagnostic ability of conventional ultrasound to diagnose manica flexoria tear in the horse by flexing the limb and applying pressure axially to the lateral and medial aspect of the proximal digital flexor tendon sheath pouches.

With this technique, location of manica flexoria tears were predicted accurately in almost 92% of cases2. Ultrasound is an easily accessible and economical modality that remains an excellent tool to monitor tendon healing and clinical response to therapy and rehabilitation3.

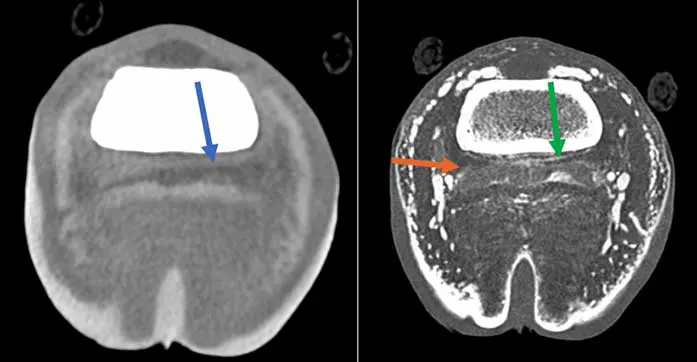

Colour or Doppler ultrasound has also helped differentiate more acute versus chronic injuries in tendinopathy in horses. In an experimental study, blood flow was increased in surgically created lesions on superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) for up to 23 weeks. While further studies are still needed, and taking into consideration the wide operator variability when using Doppler, it can be a useful method to determine the clinical relevance of a lesion and subjectively determine its stage of healing4. (Figure 2).

Doppler ultrasound has to be performed on non-weight bearing limbs. Examination usually starts with obtention of longitudinal views, combined with transverse views, and avoiding pressure. Most normal tendons should have no Doppler signal.

Ligaments (including suspensory ligaments) can have occasional vessels, and the DDFT has normal vessels at specific sites, so this should be taken into consideration when interpreting Doppler images.

Although healthy mature tendons are poorly vascularised due to low metabolic requirements, secondary hypervascularisation caused by inflammation is seen and may be detected by Doppler. A few publications have looked at the use of Doppler ultrasound for evaluation of the equine SDFT and found that it was superior to greyscale ultrasound for providing information about the healing process, and concluded it may be useful in the early detection and prevention of injury5.

Ultrasound elastography has also been described and is a technique that estimates strain – by applying compression to the limb with the ultrasound probe, tissue displacement is measured. While it is not possible to predict injury with greyscale ultrasound, it was postulated that the use of this technique may enable clinicians to manage rehabilitation and return to training in a more effective way.

In one study, while most commonly tendinous pathology of the distal limb could be detected, its use was limited for small proximal injuries of the hindlimb suspensory ligament6.

Nuclear medicine: scintigraphy and PET

Nuclear scintigraphy is an advanced diagnostic modality involving IV injection of a radiopharmaceutical agent to the patient and the use of a radiation detector or gamma camera to obtain images.

The distribution of the radiopharmaceutical agent is dependent on both osteoblastic activity and blood flow. Vascular, or soft tissue phase, is sometimes used in horses and for this purpose, images should be made five to 10 minutes after injection; therefore, this method will be limited to a very specific region, as guided by the clinical and lameness examination.

Soft tissue phases can be useful in evaluating areas of active inflammation and increased blood flow. The changes will be non-specific and, due to the time limitation, restricted to a specific region to be imaged.

PET

PET is a cross-sectional nuclear medicine modality. Similar to planar nuclear scintigraphy, it involves the injection of a radio marker, in this case a radioactive glucose, to obtain a 3D image.

While originally performed under general anaesthesia, PET scanning can now be performed in standing horses.

By providing cross-sectional images, PET has the advantage of giving more specific localisation of lesions. It also has the ability to detect changes that may occur prior to structural damage and, therefore, is often referred to as functional imaging. It is commonly performed in horses in combination with CT and MRI, which helps better interpretation of clinical usefulness of findings while providing additional information. This modality can be viewed as enhanced bone scintigraphy; it is able to diagnose more abnormalities than conventional nuclear scintigraphy, with the added advantage of being able to quantify the lesion.

PET can also be particularly useful when combined with other modalities such as CT and MRI to stage soft tissue lesions – particularly to detect metabolically active tendinopathy and monitor healing. Only DDFT lesions with increased glucose metabolism may be detected with PET. This modality is also particularly useful to assess healing of soft tissue lesions and monitoring recurrence.

Suspensory or collateral ligament enthesopathies may be particularly suited to PET due to its functional component. Measurement of standardised uptake value (SUV) is the most commonly used value to assess lesions. Normal tendons will usually have a SUV maximum value of one or lower, while tendons with lesions will range from three to five.

Some further studies are needed, but it is also thought that PET may be useful in identifying lesions that are more prone to heal or respond to treatment7.

MRI

MRI has been and likely remains the modality of choice for evaluation of lameness originating from the foot where radiographs and ultrasound have not been able to yield a complete diagnosis.

Accurate localisation of the lameness should be performed prior to performing MRI, as usually this modality looks at specific regions (foot versus pastern, versus fetlock). It is usually recommended to perform diagnostic anaesthesia, and additional use of intra-articular nerve block, as needed, should also be performed to narrow the region to be evaluated as accurately as possible and limit the costs and time required to acquire images.

MRI is commonly being used to evaluate pathology of the foot, but can also be useful in imaging other regions such as the fetlock or the origin of the suspensory8,9.

A recent publication looked at the use of MRI for DDFT pathology in the horse and highlighted that while the MRI can accurately assess the extent of tendinous lesion, it cannot determine the chronicity of it, which is an important limitation of most modalities. It has also shown that STIR and T2-weighted sequences are crucial for longitudinal monitoring of tendon injuries. This study also highlighted the importance of the use of advanced diagnostic imaging early on in the management of the disease to be able to obtain the best clinical outcome.

Studies have shown a better prognosis for return to work for horses having a tendinopathy diagnosis made within 8 to 12 weeks of the onset of lameness10.

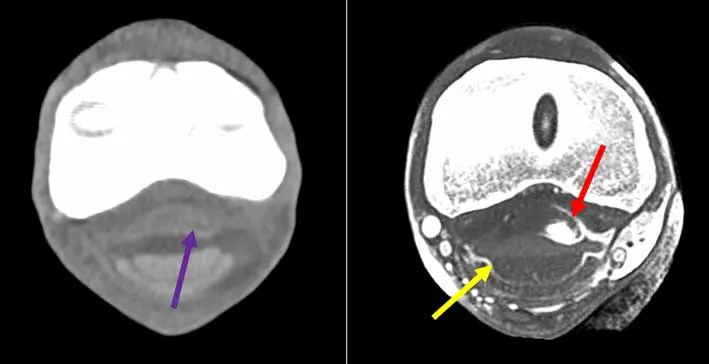

CT

CT for evaluation of distal limb pathology has also increased over the past few years. It has been commonly indicated for evaluation of horses with pain associated with the proximal aspect of the third metacarpal/metatarsal region that does not improve with conservative management.

Publications have already demonstrated the usefulness of CT for evaluation of horses suspected with proximal suspensory desmitis where high-field MRI is not readily available; this modality can reliably detect osseous proliferation, sclerosis, soft tissue enlargement and avulsion fractures11,12.

More recently, the increased availability of standing CT has seen its use increased for diagnosing pathology of the distal limb for both bone and soft tissue pathology.

One of the main advantages of using standing CT is the ability to scan more than one region at a time as opposed to MRI. This is particularly advantageous for DDFT lesions, as it is recognised that very often it affects more than one region – foot and pastern or fetlock, for example (Figure 3) – and for horse with equivocal blocking pattern. Additionally, the use of IV or intrathecal contrast has improved the soft tissue enhancement capacity of CT, making it attractive to identify most distal limb tendinopathy (Figure 4), and has increased ability to diagnose mineralisation compared to MRI13.

Care must be taken, as with lower resolution machines there is potential to overlook some lesions, in particular around the navicular bone. In a study specifically looking at tendon healing using multimodality advanced imaging, MRI and CT correlated most closely to cellular characteristics of damaged tendons, while CT was better at picking up scar tissue deposition10. Further studies are needed to see whether CT is superior to MRI for diagnosing specific tendinopathies and what pathologies are best diagnosed by which modality.

Update on treatment options

While some advances have been made in treatment options for tendon lesions, the general principles of tendon management remain the same. Treatment options are mostly guided by the healing phase of the tendon injury.

In the acute (inflammatory) phase of tendon healing, modalities that should be considered include physical therapy (hot and cold, immobilisation or compression), immediate controlled mobilisation, anti-inflammatory medication and certain surgical treatments, if appropriate (check ligament desmotomy, for example).

In the subacute (fibroblastic) phase, the aim is to stimulate extracellular tendon matrix synthesis and this is mostly achieved through regenerative medicine and rehabilitation modalities.

Finally, in the chronic (remodeling) phase of tendon healing, emphasis will be placed in a rigorous controlled exercise programme and serial regular ultrasonographic or advanced modalities re-examination to ensure that the clinical response to treatment is adequate, and to see whether adjustments should be made to the treatment regimen and/or rehabilitation protocol.

No matter what treatment options are chosen, strong evidence exists that establishment of a proper rehabilitation programme is vital in obtaining optimum results, and advanced research has been conducted in that area in various species. Controlled exercise remains a very important aspect of treatment of tendinopathy and should be adapted to the clinical response throughout the rehabilitation period. Additionally, therapeutic modalities can be added to the rehabilitation protocol and most often include the use of extracorporeal shock wave therapy, light amplification by simulation of emitted radiation (LASER) and therapeutic ultrasound14,15.

Some recent publications have looked at the use of physical therapy for tendinopathy. One publication investigated the effects of in vivo cold therapy and bandaging on core temperature of equine flexor tendons. This study confirmed that bandaging increased flexor tendon temperatures, but only up to 35.3°C, which is well below the fibroblast cell threshold of 42.5°C. Additionally, the compression cooling system device was found to provide more rapid and consistent cooling than ice boots over flexor tendons16.

One recent study investigated the use of contrast therapy for cooling of the equine distal limb. Contrast therapy is the repeated and alternating applications of both cold and heat to a region; it aims at improving post-exercise recovery and treating acute soft tissues by increasing blood circulation through cyclic vasodilation and vasoconstriction. This modality was effective in changing temperature subcutaneously, but also at the depth of the SDFT and DDFT. However, tissues deep to the DDFT did not reach target temperatures; temperatures as low as 9°C and as high as 44°C were recorded. While this may be an attractive modality in the future, research into optimal dosage parameters and timing relative to the phase of tissue healing, injury severity and affected tissues or location will be needed17.

Some recent publications regarding the use of LASER for treatment of tendon injuries have also been published.

LASERs are commonly used in equine practice. Class III and IV are most commonly used in equine rehabilitation. They have a range of less than 500mW and their wavelengths vary from 540nm to 1,060nm. LASER stimulates cell growth/metabolism, improves cell regeneration, increases fibroblastic activity and modulate inflammation by acting on prostaglandin E2, tumour necrosis factor-a, interleukin-1b, plasminogen activator, and cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2.

LASER increases serotonin, which is an excitatory neurotransmitter peripherally and also works in dorsal horn to modulate pain response providing a general feeling of well-being.

It also increases the release of beta-endorphin, which results in the increased production of endogenous opioids.

Finally, it increases acetylcholine, which is an inhibitory neurotransmitter resulting in the decrease discharge frequency of excitatory neurons and increases the frequency of inhibitory neurons; this results in a significantly increased pain threshold required for the transmission of sensory nerve input. The main indications for LASER use in equine practice are performance maintenance, prevention of injury recurrence, tendon and ligament injury, and pain relief18.

A few publications investigated the efficacy of high-power LASER on a suspensory ligament lesion model. In a first study, LASER was shown to improve vascularisation, as demonstrated by the increased Doppler signal in treated limb compared to control. It also demonstrated a lower short-term enlargement of the lesion circumference in treated limb versus control19.

Similarly, in another study, lesion size and nuclei density were found to have better scores in the treated limbs versus control20.

Regenerative medicine

Biologics and regenerative medicine therapeutic are a growing area of equine performance practice. Some of the common biologicals used in tendinopathy treatment will be listed in the remainder of this article, with some recent associated publications.

Platelet-rich plasma

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a processed orthobiologic obtained from the liquid phase of blood through centrifugation to increase platelet concentration compared with whole blood. When compared to autologous conditioned serum, it is obtained from anticoagulated blood without incubation.

PRP has been classified in different categories depending on its leukocyte count and activation status: pure PRP, which has low white blood cells (WBC) and is not activated; non-activated leukocyte-rich PRP; pure platelet-rich fibrin that has low WBC and is activated; and activated leukocyte-rich platelet-rich fibrin. The most common indications for PRP therapy are tendon and ligament lesions, followed by joint therapy.

A recent publication looking at a systemic review in the efficacy of PRP in treatment of equine tendon and ligament injury identified evidence to support it use. This publication confirmed the safety of use of PRP treatment. Overall, PRP has been shown to improve lameness scores, ultrasonographic appearance and return to competition rates compared to controls. Most studies, however, lacked information on leukocytes concentration, which is an area of a ongoing research.

As for other therapeutic options, great variability in protocols is used, either in the volume or frequency of administration; therefore, further studies are needed to refine these protocols21.

Bone marrow aspirate

Aspiration of bone marrow is usually performed from the sternum in horses. Other sites include the tuber coxae in horses three years of age or younger and the wing of the ilium. This provides components desired for tissue regeneration, including a scaffold, cells and bioactive signa. Among those, mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) can be found in low quantity in bone marrow concentrate (BMC); recently, it was shown, however, that both MSC secretome and BMC can recruit MSCs. Although further studies are needed, good evidence exists in the literature that autologous MSCs improve tendon repair in the horse.

At this time, the mode of action is still uncertain, but differentiation into tendon cells and regeneration of tendon tissue and modulation of inflammation, and resulting repair process or both, are the proposed mechanism to date.

One study demonstrated that intralesional BM-MSC treatment was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of returning to racing, compared to controlled exercise and rehabilitation alone22.

Conclusion

While some advancement has been made in treatment options for tendinopathies in horses, further scientific evidence is still needed – especially on the biologics.

However, a lot of promise can be found on the advanced imaging side.

It will be interesting to see how the standing CT compares versus MRI in the future and whether standing CT may be used for monitoring of lesion healing and adapting rehabilitation protocol, to allow a better return function and a decreased re-injury risk.

- Article appeared in Vet Times (2026), Volume 56, Issue 01, Pages 14-17

- Mélanie Perrier graduated in France, then went on to complete a surgical internship, followed by a surgery residency, in the US. She was then a clinical assistant professor on equine surgery at the University of Tennessee, before returning to private practice in the Middle East and France. Mélanie is a lecturer in equine surgery at the RVC.

More on this equine topic

Good physical exam: what we can learn from palpation and flexion

References

- 1. Kent AV, Chesworth MJ, Wells G, Gerdes C, Bladon BM, Smith RKW and Fiske-Jackson AR (2019). Improved diagnostic criteria for digital flexor tendon sheath pathology using contrast tenography, Equine Vet J 52(2): 205-212.

- 2. Hibner-Szaltys M, Cavallier F, Cantatore F, Withers JM and Marcatili M (2023). Ultrasonography can be used to predict the location of manica flexoria tears in horses, Equine Vet Educ 35: e200-e207.

- 3. Iimori M, Tamura N, Seki K and Kasashima Y (2022). Relationship between the ultrasonographic findings of suspected superficial digital flexor tendon injury and the prevalence of subsequent severe superficial digital flexor tendon injuries in thoroughbred horses: a retrospective study, J Vet Med Sci 84(2): 261-264.

- 4. Tamura N, Yoshihara E, Seki K, Mae N, Kodaira K, Iimori M, Yamazaki Y, Mita H, Urayama S, Kuroda T, Ohta M and Kasashima Y (2024). Prognostic value of power doppler ultrasonography for equine superficial digital flexor tendon injury in thoroughbred racehorses, Vet J 306: 106179.

- 5. Lacitignola L, De Luca P, Santovito R and Crovace A (2019). Power Doppler to investigate superficial digital flexor tendinopathy in the horse, Open Vet J 9(4): 317-321.

- 6. Lustgarten M, Redding WR, Labens R, Davis W, Daniel TM, Griffith E and Seiler GS (2015). Elastographic evaluation of naturally occurring tendon and ligament injuries of the equine distal limb, Vet Radiol Ultrasound 56(6): 670-679.

- 7. Spriet M and Vandenberghe F (2024). Equine nuclear medicine in 2024: use and value of scintigraphy and PET in equine lameness diagnosis, Animals 14(17): 2,499.

- 8. Ehrle A, Lilge S, Clegg PD and Maddox TW (2021). Equine flexor tendon imaging part 2: current status and future directions in advanced diagnostic imaging, with focus on the deep digital flexor tendon, Vet J 278: 105763.

- 9. Berner D (2017). Diagnostic imaging of tendinopathies of the superficial flexor tendon in horses, Vet Rec 181(24): 652-654.

- 10. Scharf A, Acutt E, Bills K and Werpy N (2025). Magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing and managing deep digital flexor tendinopathy in equine athletes: insights, advances and future directions, Equine Vet J 57(5): 1,183-1,203.

- 11. Johnson SA, Valdés-Martínez A, Turk PJ, McIlwraith CW, Barrett MF, McGilvray KC and Frisbie DD (2021). Longitudinal tendon healing assessed with multi modality advanced imaging and tissue analysis, Equine Vet J doi: 10.1111/evj.13478. Online ahead of print.

- 12. Lee S, Shin K-Y, Lee K and Seo J-P (2025). Intra-arterial contrast enhanced computed tomography of the deep digital flexor tendon and palmar veins in the distal forelimb in Jeju horses: evaluating contrast enhancing factors, Equine Vet J 57(3): 789-797.

- 13. Pauwels F, Hartmann A, Alawneh J, Wightman P and Saunders J (2021). Contrast enhanced computed tomography findings in 105 horse distal extremities, J Equine Vet Sci 104: 103704.

- 14. Boström A, Bergh A, Hyytiäinen H and Asplund K (2022). Systematic review of complementary and alternative veterinary medicine in sport and companion animals: extracorporeal shockwave therapy, Animals 12(22): 3,124.

- 15. Atalaia T, Prazeres J, Abrantes J and Clayton HM (2021). Equine rehabilitation: a scoping review of the literature, Animals 11(6): 1,508.

- 16. McCarthy RD, Ordóñez HJ and Semevolos SA (2025). In vivo effects of cold therapy and bandaging on core temperatures of equine superficial and deep digital flexor tendons, Vet Surg 54(3): 470-477.

- 17. Haussler KK, Wilde SR, Davis MS, Hess AM and McIlwraith CW (2021). Contrast therapy: tissue heating and cooling properties within the equine distal limb, Equine Vet J 53(1): 149-156.

- 18. Zielińska P, Nicpoń J, Kiełbowicz Z, Soroko M, Dudek K and Zaborski D (2020). Effects of high intensity laser therapy in the treatment of tendon and ligament injuries in performance horses, Animals 10(8): 1,327.

- 19. Pluim M, Martens A, Vanderperren K, van Weeren R, Oosterlinck M, Dewulf J, Kichouh M, Van Thielen B, Koene MHW, Luciani A, Plancke L and Delesalle C (2020). High power laser therapy improves healing of the equine suspensory branch in a standardized lesion model, Front Vet Sci 7: 600.

- 20. Pluim M, Heier A, Plomp S, Boshuizen B, Gröne A, van Weeren R, Vanderperren K, Martens A, Dewulf J, Chantziaras I, Koene M, Luciani A, Oosterlinck M, Van Brantegem L and Delesalle C (2022). Histological tissue healing following high power laser treatment in a model of suspensory ligament branch injury, Equine Vet J 54(6): 1,114-1,122.

- 21. Carmona JU and López C (2025). Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of equine tendon and ligament injuries: a systematic review of clinical and experimental studies, Vet Sci 12(4): 382.

- 22. Bernardino PN, Smith WA, Galuppo LD, Espinosa-Mur P and Cassano JM (2022). Therapeutics prior to mesenchymal stromal cell therapy improves outcome in equine orthopedic injuries, Am J Vet Res 83(10): ajvr.22.04.0072.