6 Jan 2026

Nutrition: cause and management of companion animal diseases

Mike Davies BVetMed, CertVR, CertSAO, FRCVS provides a definitive guide to nutrients and their effects.

Image: Tatyana Gladskih / Adobe Stock

Globally, the pet food market is a multi-billion dollar business, estimated at approximately US$126.66 billion (£95 billion) in 2024 and projected to grow to US$193.65 billion (£145.12 billion) by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate of 5.52% during this period.

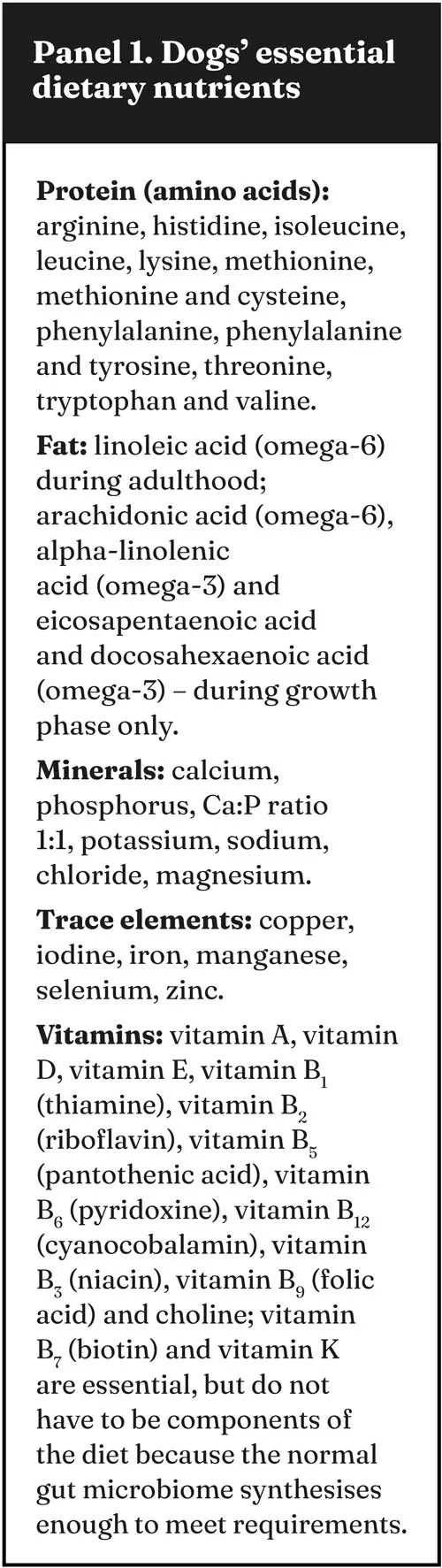

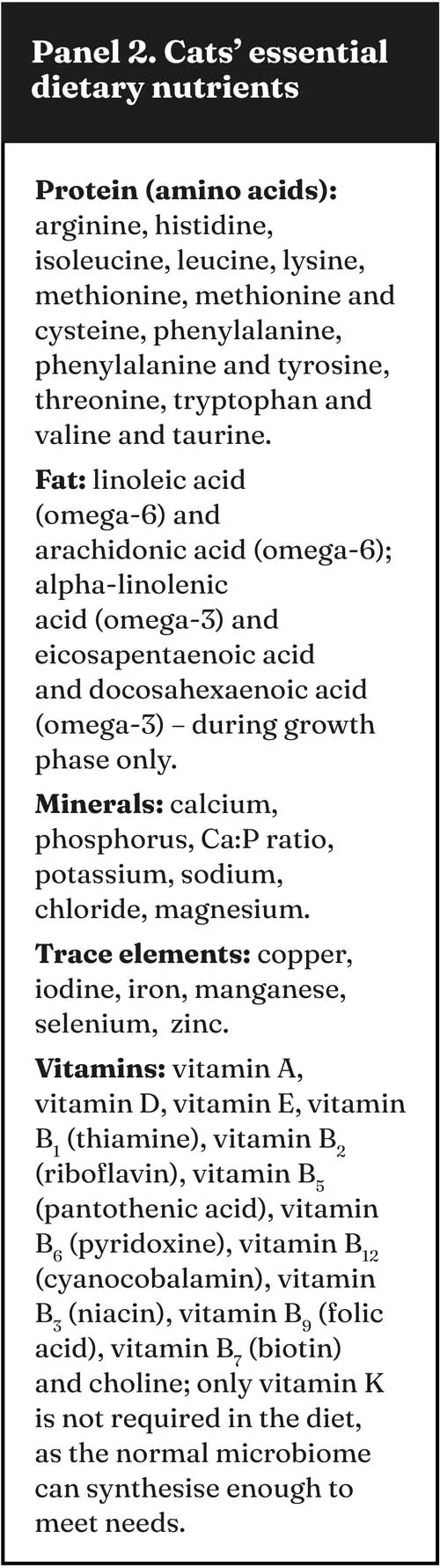

The National Research Council (NRC) has determined the essential nutrients that need to be supplied in the ration of a dog or cat because they are unable to synthesise sufficient amounts. The European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF) cites 37 essential dietary nutrients for dogs (Panel 1) and 41 for cats (taurine, arachidonic acid and biotin are the additional feline essential nutrients; Panel 2).

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common in people (Kiani et al, 2022) and pets, and they can be caused by the following issues.

Inadequate amounts of a nutrient in the ration

Numerous studies have shown that current pet foods frequently fail to meet FEDIAF minimum nutritional guidelines.

Pet foods labelled as being “complete” are meant to comply with FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines, and so meet all the nutritional needs of the animals they are intended for. Unfortunately, studies have shown that the vast majority of pet foods sold as complete in the UK do not comply with FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines, with only 6% (6 out of 97) of wet and 38% (30 out 80) of dry food being fully compliant for minerals and trace elements (Davies et al, 2017).

In another study looking at insect-based pet foods, numerous failures in compliance were found, including fatty acid content (Ryu et al, 2024). Meanwhile, studies looking at vegan pet foods showed poorly formulated brands failed to comply (Zafalon et al, 2020).

In one study (Zafalon et al, 2020), one of three commercial vegan dog foods had a content of zinc more than the EU legal limits; whereas, zinc content of home-prepared diets was below the nutritional requirements in 79% of 75 recipes of dog foods available on the internet. More than half of raw pet foods analysed (Dillitzer et al, 2011) failed to supply the daily recommended allowance of zinc.

Homemade rations have been shown to be unreliable, even when formulated by qualified veterinary nutritionists (Larsen et al, 2012; Davies, 2014).

More on nutrition in cats and dogs

Poor bioavailability

Poor bioavailability can be a result of:

- Impaired digestion. Dogs and cats with chronic pancreatic disease (for example, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or reduced bile secretion) may not be able to digest nutrients properly, typically resulting in malabsorption, nutrient deficiency, diarrhoea and steatorrhoea. Minerals such as phosphorus that are bound as phytates in some plants cannot be digested and made available because dogs and cats lack the phytase enzymes necessary.

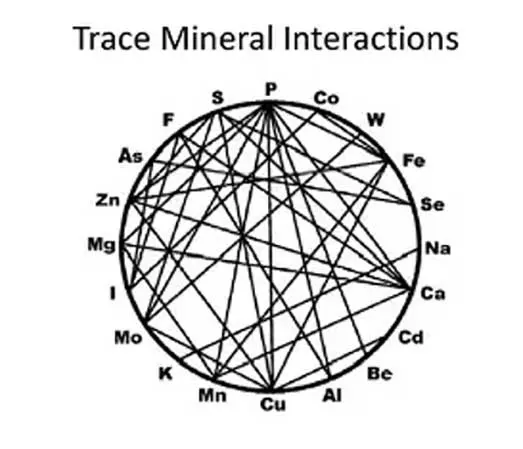

- Competition from other nutrients in the intestine lumen. For example, mineral interactions (Figure 1). Minerals can compete with each other and impair bioavailability; for example, copper deficiency can occur even if enough copper is present in the food, when too much zinc is also present in the food.

- Impaired absorption. The presence of high fibre can also reduce bioavailability of essential nutrients by binding with them or blocking access to receptors. This means that chemical analysis of pet foods does not guarantee adequate bioavailability. Dogs with chronic gastrointestinal disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), may not be able to absorb nutrients from the lumen. So, for example, clotting defects due to vitamin K deficiency can occur, and thiamine deficiency is apparently common in IBD for this reason.

- Impaired transportation. Nutrients have to be transported into and around the body bound to other substances; for example, fat-soluble vitamins are bound to fats, and many others are bound to proteins (triglyceride transport protein is needed to move fats out from enterocytes).

- Increased losses. Electrolytes can be lost in diarrhoea or vomit, and polyuria results in excessive losses of water-soluble nutrients – especially the water-soluble vitamin B complex.

Impaired biochemical utilisation

Other categories at high risk include dogs or cats with diabetes mellitus, which results in hyperglycaemia, but also other metabolic changes, chronic inflammatory disease and other conditions that alter biochemical pathways.

Insufficient synthesis

Taurine is an essential dietary constituent for cats, but it is not for dogs because they can synthesise enough from sulphur-containing amino acids methionine and cystine.

However, dogs can develop taurine deficiency with clinical signs such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) if the diet is deficient in the essential amino acids required. Taurine deficiency in cardiac muscle can also occur if transportation into the cells is impaired.

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched an investigation into a possible link between pet foods and taurine deficiency DCM in dogs. This created a lot of public concern. It announced that its findings have not established a direct causal relationship between diets and DCM. (Wall, 2022).

Nutrient excesses

Most essential nutrients are not toxic when consumed in large amounts, but some are – mainly minerals, trace elements and fat-soluble vitamins A, D and E. FEDIAF has set maximum limits, nutritional or legal, for some nutrients (FEDIAF, 2025).

Nutrients for which FEDIAF specifies upper limits

- Dogs: vitamin A, vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, Ca:P ratio, copper iodine, iron, manganese, selenium, zinc. Also, lysine and linoleic acid, only during the growth phase.

- Cats: vitamin A, vitamin D, Ca:P ratio, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, selenium, zinc. Also, arginine, methionine and tryptophan during the growth phase.

Pets most susceptible to nutrient deficiencies, excesses or imbalances are the young, those being fed homemade, raw meat or inappropriately formulated vegan diets, and those with subclinical or clinical diseases.

Common diseases

The following list includes some of the nutrient deficiencies, excesses or imbalances associated with clinical signs in dogs and cats, alongside key references.

Protein

- Skin problems and pruritus, hormonal imbalances, poor growth, stunted growth, behavioural changes including lethargy and aggression, signs of various amino acid deficiencies (Che et al, 2021; Li and Wu, 2023; NRC, 2006).

- Arginine. In dogs – growth impaired, reduced appetite, hyperammonaemia, hyperglycaemia, seizures, vomiting, excessive salivation and muscle tremors, cataract (puppies). In cats – reduced appetite, reduced growth, hyperammonaemia, vomiting, neurological signs, ataxia, tetanic spasms, and death (Ha et al, 1978; Morris and Rogers, 1978; Burns and Milner, 1981; Ranz et al, 2002; Li and Wu, 2023; Dor et al, 2018; NRC, 2006).

- Histidine. In dogs – reduced activity, listlessness, death. In cats:c ataracts (kittens) (Cianciaruso et al, 1981; Quam et al, 1987; NRC, 2006).

- Isoleucine. In dogs – muscle weakness, fatigue. In cats – poor growth, reproductive problems. In kittens – weight loss, impaired resistance to infection, incoordination (ataxia), porphyrin-like staining around the eyes, nose and mouth, sloughing of paw pads (Li and Wu, 2023; Hargrove et al, 1984; NRC, 2006).

- Leucine. Muscle weakness, muscle wastage, lethargy, poor appetite, weight loss (NRC, 2006).

- Lysine. Poor growth, weight loss, reduced immune response, lethargy, skin and coat issues, dull fur (Sutherland et al, 2020; NRC, 2006).

- Methionine and cystine. In puppies – decreased food intake, weight loss, dermatitis, hyperkaratotic, necrotic foot pad lesions. In adult dogs – taurine-deficient cardiomyopathy and pigmented gallstones. In kittens – weight loss, lethargy, abnormal ocular secretions, severe perioral and foot pad lesions. (Milner, 1979; Burns and Milner, 1981; Christian and Rege, 1996; Teeter et al, 1978; NRC, 2006; Rogers and Morris, 1979).

- Phenylalanine and tyrosine. In puppies – decreased food intake and weight loss. In adult dogs –reddening of haircoat. In kittens – weight loss, reddening of the haircoat, ataxia, vocalising, ptyalism, hyperactivity, abnormal tail posture (tail held bent forward; Milner et al, 1984; Biourge and Sergheraert, 2002; Rogers and Morris, 1979; Yu et al, 2001; NRC, 2006).

- Thiamine. In dogs and cats.

- Phase 1 (1-2 weeks): vomiting, lethargy, hyporexia or anorexia, weight loss.

- Phase 2: (2-4 weeks): ataxia, paraparesis, nystagmus, delayed pupillary light response and blindness, recumbency, poor proprioception, seizures. Cats also get cervical ventroflexion, dyspnoea, arrhythmias and bradycardia.

- Phase 3 (up to 30 days): rapid worsening of signs until death (Kritikos et al, 2017; Houston and Hulland, 1988; Singh et al, 2005; NRC, 2006).

- Threonine. In dogs – decreased food intake, weight loss. In kittens – decreased food intake, weight loss, ataxia, tremors, incoordination (Burns and Milner, 1982; Rogers and Morris, 1979; Titchenal et al, 1980; NRC, 2006).

- Tryptophan. In puppies and kittens – decreased food intake, weight loss (Burns and Milner, 1982; Rogers and Morris, 1979; NRC, 2006).

- Valine. In puppies and kittens – reduced food intake, weight loss (Butterwick et al, 2015a; NRC, 2006).

Fat

- Linoleic acid (LA; during adulthood). Kittens fed LA-deficient diets fail to grow normally and develop course dull hair coats. Puppies fed LA-deficient diets develop coarse, dry hair coats, with skin flaking after two months (Sinclair et al, 1981; Rivers, 1982; Weise et al, 1962; NRC, 2006).

- Linoleic acid (omega-6). Dull, dry hair coat.

- Arachidonic acid (omega-6). In queens – unable to support normal pregnancy and fetal development (MacDonald et al, 1984; NRC, 2006).

- Alpha-linolenic acid (omega-3). None reported.

- Eicosapentaenoic acid or docosahexaenoic acid (omega-3; during growth phase only). None reported.

Minerals

- Calcium.

- Deficiency: in puppies and kittens – poor ossification of the skeleton with thin bone cortices and spontaneous fractures.

- Adult cats and dogs: nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, muscle twitching, spasms, loss of appetite, stiffness, lethargy, changes in behaviour, such as restlessness, eclampsia (milk fever).

- Toxicity: osteochondrosis, stunted growth, premature closure of growth plates, angular limb deformities, metastatic calcification of soft tissues (Schoenmakers et al, 1999; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Phosphorus.

- Deficiency: in puppies – poor growth, skeletal abnormalities – rickets, osteoporosis, pica. In adults – osteoporosis, tooth loss, fractures, decreased cardiac function, platelet and red blood cell dysfunction.

- Toxicity: nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, demineralisation of skeleton, fractures, bone pain, soft tissue calcification, progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD; Schoenmakers et al, 1999; Fuller et al, 1978; Yawata et al, 1974; Kidder and Chew, 2009; Alexander et al, 2019; Dobenecker et al, 2018; NRC, 2006; McDowell 1992).

- Ca:P ratio. Impaired endochondral ossification, skeletal abnormalities, demineralisation of skeleton, osteoporosis, fractures (NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Potassium.

- Deficiency: in puppies – muscle weakness, paralysis and poor growth. In adult dogs – decreases in blood pressure, cardiac output, stroke volume and renal blood flow. In cats – paralysis and poor growth, anorexia, retarded growth and neurological disorders, neck ventroflexion, ataxia, muscle weakness, hypokalaemia.

- Toxicity: bradyarrhythmia with ECG changes of tented T waves, short QT interval, prolonged PR interval, widening of QRS complex, decreased amplitude and widening of P waves (Abbrecht, 1972; Dow et al, 1987; Dow et al, 1990; Leon et al, 1992; Ruegamer et al, 1946; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Sodium.

- Deficiency: hyponatraemia – only if associated with a metabolic issue in the animal; cannot be induced by diet restriction alone.

- Toxicity: hypertension (Burton and Hopper, 2019; Freeman et al, 2006; Ueda et al, 2015; Spangler 1979; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Chloride.

- Deficiency: in puppies and kittens – weakness, ataxia, stunted growth (Butterwick et al, 2015b NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Magnesium.

- Deficiency: muscle weakness, tremors, heart arrhythmias, hypomagnesaemia (only experimentally; Schulz et al, 2018; Mellema and Hoareau, 2014; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

Trace elements

- Copper.

- Deficiency: loss of hair colour, reduced fertility, impaired cellular immune response, impaired connective tissue integrity, anaemia.

- Toxicity: decreased liver function, haemolysis, cellular and tissue necrosis, Hepatitis, cirrhosis (Amundson et al, 2024; Zentek and Meyer, 1991; Thornburg, 2000; Center et al, 2021; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Iodine.

- Deficiency: hypothyroidism, characterised by lethargy, weight gain, skin and coat problems, such as hair loss and dryness.

- Excess: hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, weight loss, aggressiveness, tachycardia, panting and restlessness (Nuttall, 1986; Köhler et al, 2012; Guidi et al, 2022; Peixoto et al, 2012; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Iron.

- Deficiency: in dogs and cats –anaemia (microcytic, hypochromic), lethargy, decreased exercise tolerance, weakness, weight loss, retarded growth, generalised malaise, pica, melaena, haematuria, haematochezia, bleeding, bounding pulses, arrhythmia, systolic heart murmur.

- Toxicity: vomiting, diarrhoea, gastrointestinal bleeding, gastrointestinal strictures, lethargy, metabolic acidosis, shock, hypotension, tachycardia, cardiovascular collapse, coagulation deficits, hepatic necrosis, death (Naigamwall et al, 2012; Harvey, 2008; Giger, 2005; Weiss, 2010; Greentree and Hall, 1995; Albretsen, 2006; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Manganese. Not reported on dogs or cats, causes developmental bone disease in other species (Butterwick et al, 2015c; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Selenium.

- Deficiency: hypothyroidism, autoimmune disease (Sahebari et al, 2019; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

- Zinc.

- Deficiency: anorexia, poor growth, impaired immune responses, skin lesions located in the face, head and paws, parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, lethal acrodermatitis. Zinc-responsive dermatosis – crusts, alopecia, pruritus, erythema. Behavioural problems – excessive activity, aggression towards people and dogs, destructiveness, inappropriate elimination, fearfulness.

- Toxicity: often ingested zinc-containing foreign objects. Anaemia, vomiting, hyperbilirubinaemia, lethargy, decreased appetite (anorexia), diarrhoea, haemolytic anaemia, haemoglobinuria, Heinz bodies, spherocytes, hyperbilirubinaemia, haemolysis, liver dysfunction, high serum activities of liver-associated enzymes (such as alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase), pancreatitis (pancreatic fibrosis and acinar necrosis), coagulopathies, acute kidney failure (associated with diffuse tubular degeneration with focal epithelial necrosis; Pereira et al, 2021; McEwan et al, 2000; Colombini, 1999; White et al, 2001; van den Broek and Thoday, 1986; Lee et al, 2016; Soltanian et al, 2016; Zafalon et al, 2020; Pedrinelli et al, 2019; Bauer et al, 2018; Gurnee and Drobatz, 2007; Blundell and Adam, 2013; Bischoff et al, 2017; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1992).

Vitamins

- Vitamin A.

- Deficiency: nyctalopia, reduced vision in low light, conjunctivitis, xerosis with keratitis and corneal neovascularisation, photophobia, mydriasis in normal lighting, delayed pupillary light reflex, progressive retinal cell degeneration, cataract formation, blindness, altered mental state, seizures, nystagmus, ataxia, kyphosis, hyperaesthesia, muscle wasting, nerve degeneration, impaired nerve conduction, weight loss, bronchial epithelial metaplasia, squamous metaplasia in the salivary glands and endometrium, a dry and lacklustre coat, dermatological issues, compromised immune function, reproductive complications such as infertility or dystocia.

- Toxicity: during pregnancy – congenital deformities including cleft palate, gross skeletal deformities; diarrhoea, loss of appetite, lethargy, weakness, disorientation, seizures, bone demineralisation, periarticular exostoses, reduced range of movement of joints, lameness and joint pain, reduced thyroxine levels in the blood plasma, signs of copper deficiency (Shastak and Pelletier, 2024; Stimson and Hedley, 1933; Espadas et al, 2017; Scott et al, 1964; Olcott, 1933; Verstegen et al, 2008; Mellanby, 1926; Green and Mellanby, 1928; Ihrke and Goldschmidt, 1983; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1989; Abadie et al, 2023.

- Vitamin D.

- Deficiency: nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, poor skeletal mineralisation, hypocalcaemia, classic rickets, bone pain, stiff gait, metaphyseal swelling, bowed limbs, fractures, and low serum vitamin D and calcium concentrations, lethargy, weakness, muscle tremors, bone pain and stiffness, impaired immune system, cardiovascular issues, potential heart failure, neuromuscular problems.

- Toxicity: lethargy, polydipsia and polyuria (due to hypercalcaemia), stiff gait, soft tissue mineralisation (Corbee, 2020; NRC, 2006; De Fornel-Thibaud et al, 2007; Mellanby et al, 2005; Clarke et al, 2021; McDowell 1989).

- Vitamin E. In dogs – anorexia, reproductive failure (male sterility), skeletal and endocardial muscle degeneration, retinal degeneration, dermatitis, subcutaneous oedema, haemolysis, immunodeficiency. In cats – anorexia, depression, myopathy, pansteatitis.

- Toxicity: prolonged bleeding times in cats (Chow, 2000; NRC, 2006; Brigelius-Flohé and Traber, 1999; Elvehjem et al, 1944; Van Vleet, 1975; Davidson et al, 1998; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B1 (thiamine). In dogs – heart failure, tachycardia/bradycardia, emaciation, paralysis, anorexia, progressive spastic paraparesis, recumbency, convulsions, sterility (male), death. In cats – lack of appetite, vomiting, weight loss, neurological signs (altered mentation, acute blindness, proprioceptive deficits, ataxia, polyneuropathy, spastic ventroflexion of the head and neck, extensor rigidity, vestibular signs, paresis, hyperaesthesia, tremors, seizures, coma), ocular (acute blindness, mydriasis or anisocoria, nystagmus), gastrointestinal tract (anorexia or hyporexia, weight loss, vomiting, constipation; NRC, 2006; Kritikos et al, 2017; Swank et al, 1941; Read et al, 1977; Markovich et al, 2013; Hackel et al, 1953; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B3 (niacin). In dogs – anorexia, dehydration, diarrhoea, dullness, gingivitis, glossitis, oral cavity ulcers, poor growth rate, excessive salivation and drooling, vomiting, weight loss, death in untreated cases. In cats – anorexia, diarrhoea, dullness, glossitis, oral cavity ulcers, poor coat (lack of grooming), respiratory distress, death in untreated cases (Provet, 2013; Redzic et al, 2023; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B2 (riboflavin): In puppies – impaired growth, anorexia, weight loss, weakness, ataxia, collapse, death. In adult dogs and cats – bilateral corneal opacities, anorexia, weight loss, periauricular alopecia, bilateral cataracts, testicular hypoplasia, fatty accumulation in the liver, death (Axelrod et al, 1940; Noel et al, 1972; Street and Cowgill, 1939; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid). Growth impairment, reduced appetite, immune suppression, paralysis, coma, convulsions. In kittens – emaciation, fatty liver. In cats – growth failure, histologic changes in the small intestines and liver (NRC, 2006; Gershoff and Gottlieb, 1964; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine). In dogs – microcytic, hypochromic anaemia, appetite loss, weight loss, ataxia, cardiac dilation, cardiac hypertrophy, congestion, demyelination of peripheral nerves. In kittens – poor growth, microcytic hypochromic anaemia, seizures, kidney tubular atrophy (NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1989).

- Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin). Anorexia, weight loss, neurological symptoms, immunodeficiencies and intestinal changes including villous atrophy, malabsorption, gastrointestinal clinical signs may cause B12 deficiency (Reed et al, 2007; Fordyce et al, 2000; Gold et al, 2015; Battersby et al, 2005; Salvadori et al, 2003; Arvanitakis, 1978; McDowell, 1989; NRC, 2006).

- Vitamin B9 (folic acid). In dogs – reduced growth, reduced appetite, epiphora, glossitis, leukopenia, reduced immune response, hypochromic anaemia. In cats – weight loss, anaemia, leukopenia and prolonged blood clotting time (Ullal et al, 2023; NRC, 2006; McDowell, 1989).

- Choline. In puppies – fatty liver, thymus atrophy. In kittens – fatty liver, hypoalbuminaemia, impaired growth (McDowell, 1989; NRC, 2006).

- Vitamin B7 (biotin). In dogs and cats – weight loss, alopecia (only associated with avidin in raw egg white (McDowell, 1989; NRC, 2006).

- Vitamin K. Signs not due to dietary deficiency – due to interference with absorption, or excessive oral administration. Deficiency causes clotting defects, haemorrhage. Excess causes clotting defects, vomiting (McDowell, 1989; NRC, 2006).

- Taurine. In dogs – dilated cardiomyopathy. In cats – dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure, central retinal degeneration, blindness, deafness, poor reproduction, congenital skeletal abnormalities (Freeman et al, 2018; McCauley et al, 2020; Pion et al, 1992; NRC, 2006).

Clinical signs

The following list includes some of the clinical signs associated with nutritional deficiencies, excesses or imbalances.

Most of these are common, others uncommon, and some are rare, only occurring when cats or dogs are fed a specialised diet as in a deficiency or toxicology study.

- Activity reduced. Histidine deficiency – dogs; lysine deficiency; iron deficiency.

- Acute kidney injury. Zinc toxicity.

- Aggression. Iodine excess; zinc deficiency.

- Alopecia. Iodine deficiency; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – cats and dogs (periauricular); vitamin B7 (biotin) – dogs and cats when given egg white containing avidin.

- Anaemia. Copper deficiency; iron deficiency; phosphorus deficiency – dogs; zinc toxicity; vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs and cats; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – dogs and cats.

- Angular limb deformities. Calcium deficiency – large dogs; vitamin D deficiency.

- Anisocoria. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Appetite reduction/anorexia. Arginine deficiency – cats and dogs; leucine deficiency; lysine deficiency; lysine; methionine and cystine deficiency – puppies; phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – puppies; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; threonine deficiency – dogs and kittens; tryptophan deficiency – puppies and kittens; valine deficiency – puppies and kittens; calcium deficiency; zinc toxicity; vitamin A excess; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – dogs and cats; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid); vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency; vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency; vitamin E deficiency.

- Ataxia. Arginine deficiency – cats; isoleucine deficiency – kittens; phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – kittens; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; threonine deficiency – kittens; chloride deficiency – puppies and kittens; vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – puppies; vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency.

- Bleeding/clotting time increased. Vitamin E toxicity – cats; vitamin K deficiency; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – cats.

- Blindness. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats; taurine deficiency – cats.

- Bone cortices thinning. Calcium deficiency.

- Bone pain. Phosphorus excess; vitamin D deficiency.

- Bone undermineralisation. Calcium deficiency – cats and dogs; phosphorus excess; vitamin A excess; vitamin D deficiency – classic rickets.

- Bradyarrhythmia. Potassium excess; thiamine deficiency.

- Bronchial epithelial metaplasia. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Cardiac arrhythmia. Thiamine deficiency – cats (bradycardia); magnesium deficiency – puppies and kittens; iron deficiency.

- Cardiac dilation. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs

- Cardiac function reduced. Phosphorus deficiency.

- Cardiac hypertrophy. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs

- Cardiac murmur. Iron deficiency (anaemia).

- Cardiac muscle degeneration. Vitamin E deficiency.

- Cardiovascular collapse. Iron excess.

- Cataracts. Arginine deficiency – puppies; histidine deficiency – kittens; vitamin A deficiency; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency – dogs and cats.

- Chronic kidney disease – progression. Phosphorus excess.

- Cirrhosis. Copper excess.

- Coagulation deficits. Iron excess.

- Collapse. Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – puppies.

- Coma. Thiamine deficiency – cats; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) deficiency – dogs.

- Congenital abnormalities. Vitamin A excess – cleft palate, skeletal abnormalities; vitamin A deficiency; taurine deficiency – cats – gross skeletal abnormalities.

- Congestion. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs.

- Conjunctivitis. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Connective tissue impairment. Copper deficiency.

- Constipation. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Corneal neovascularisation. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Corneal opacities – bilateral. Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) cats and dogs.

- Deafness. Taurine deficiency – cats.

- Death. Arginine deficiency – cats; histidine deficiency – dogs; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; iron toxicity; thiamine deficiency; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – dogs and cats; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency – puppies, dogs and cats.

- Depression. Vitamin E deficiency – cats.

- Dermatitis. Lysine; methionine and cystine deficiency – puppies; vitamin E deficiency – dogs.

- Destructive behaviour. Zinc deficiency.

- Diarrhoea. Iron toxicity; zinc toxicity; vitamin A excess; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency.

- Dilated cardiomyopathy. Methionine and cystine deficiency – dogs; taurine deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs.

- Disorientation. Vitamin A excess.

- Dullness. Vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Dyspnoea. Thiamine deficiency – cats; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – cats.

- Dystocia. Vitamin A deficiency.

- ECG changes. Potassium excess.

- Eclampsia. Calcium deficiency.

- Emaciation. Thiamine deficiency.

- Endochondral ossification impairment. Calcium deficiency and excess; phosphorus deficiency and excess; abnormal Ca:P ratio.

- Endometrial metaplasia. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Epiphora. Vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – dogs.

- Extensor rigidity. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Fatigue. Isoleucine deficiency – dogs.

- Fatty liver. Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) deficiency – kittens; choline deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Fearfulness. Zinc deficiency.

- Fertility reduced. Copper deficiency.

- Foot pad lesions. Methionine and cystine deficiency – kittens.

- Foot pad necrosis. Lysine; methionine and cystine deficiency – puppies.

- Fractures. Calcium deficiency; phosphorus deficiency; phosphorus excess; abnormal Ca:P ratio; vitamin D deficiency.

- Gallstone pigmentation. Lysine; methionine and cystine deficiency – dogs.

- Gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Iron toxicity.

- Gastrointestinal strictures. Iron toxicity.

- Gingivitis. Vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – dogs.

- Glossitis. Vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – dogs.

- Growth impairment. Arginine deficiency – cats and dogs; isoleucine deficiency – cats; protein deficiency – cats and dogs; linoleic acid deficiency – kittens; calcium excess – large dogs; phosphorus deficiency; chloride deficiency – puppies and kittens; iron deficiency; zinc deficiency; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – puppies; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) – puppies and kittens; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – dogs; choline deficiency – cats.

- Growth plate premature closure. Calcium excess.

- Haematemesis. Iron deficiency.

- Haematochezia. Iron deficiency.

- Haematuria. Iron deficiency.

- Haemoglobinuria. Zinc toxicity.

- Haemolysis. Copper excess; zinc toxicity; vitamin E deficiency – dogs.

- Haemorrhage iron toxicity. phosphorus deficiency – dogs; vitamin K deficiency.

- Hair dull and coarse. Lysine deficiency; linoleic acid deficiency – puppies and kittens; iodine deficiency; vitamin A deficiency; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency (unkempt).

- Haircoat changes from black to reddish brown. Copper deficiency cats and dogs; phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – dogs and cats.

- Heart failure. Thiamine deficiency.

- Heinz bodies. Zinc toxicity.

- Hepatic necrosis. Iron toxicity.

- Hepatitis. Copper excess.

- Hyperactivity. Phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – kittens; zinc deficiency.

- Hyperaesthesia. Vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Hyperammonaemia. Arginine deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Hyperbilirubinaemia. Zinc toxicity.

- Hypercalcaemia. Vitamin D toxicity.

- Hyperglycaemia. Arginine deficiency – dogs.

- Hyperkeratosis. Lysine; methionine and cystine deficiency – puppies.

- Hypertension. Sodium excess.

- Hyperthyroidism. Iodine excess.

- Hypocalcaemia. Vitamin D deficiency.

- Hypoalbuminaemia. Choline deficiency – kittens.

- Hypotension. Iron excess.

- Hypothyroidism. Iodine deficiency; iodine excess.

- Immunity impaired – increased infections. Isoleucine deficiency – kittens; lysine deficiency; copper deficiency; zinc deficiency; vitamin A deficiency; vitamin D deficiency; vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) deficiency – dogs; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – dogs.

- Inappropriate elimination. Zinc deficiency.

- Infertility. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Joint pain. Vitamin A excess.

- Keratitis. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Kyphosis. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Lameness. Vitamin A excess.

- Leukopenia. Vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Lethargy. Leucine deficiency; lysine deficiency; methionine and cystine deficiency – kittens; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; calcium deficiency; iodine deficiency; iron deficiency; iron excess; zinc deficiency; vitamin A excess; vitamin D deficiency; vitamin D toxicity.

- Listlessness. Histidine deficiency – dogs.

- Liver function impairment. Copper excess; zinc toxicity.

- Metabolic acidosis. Iron excess.

- Mental status affected. Vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Muscle spasms. Calcium deficiency.

- Muscle tremors. Arginine deficiency – dogs; vitamin D deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Muscle twitches. Calcium deficiency.

- Muscle wastage. Leucine deficiency; vitamin A deficiency.

- Muscle weakness. Isoleucine deficiency – dogs; leucine deficiency; potassium deficiency; chloride deficiency – puppies and kittens; magnesium deficiency – puppies and kittens; iron deficiency; vitamin A excess; vitamin D deficiency; vitamin E deficiency/selenium; vitamin B2 (riboflavin) – puppies.

- Mydriasis. Vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency.

- Myopathy. Vitamin E deficiency – cats.

- Neck ventroflexion. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Neurological signs. Arginine deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin A deficiency – neural degeneration; vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency.

- Nerve demyelination. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – dogs.

- Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism. Calcium deficiency – cats and dogs; phosphorus excess; vitamin D deficiency.

- Nyctalopia – reduced vision in low light. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Nystagmus. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Ocular discharge. Methionine and cystine deficiency – kittens.

- Oral cavity ulcers. Vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Osteochondrosis. Calcium excess – large dogs.

- Osteomalacia/osteoporosis. Calcium deficiency – cats and dogs; phosphorus deficiency; phosphorus excess; abnormal Ca:P ratio; vitamin A excess.

- Pancreatitis. Zinc toxicity.

- Pansteatitis. Vitamin E deficiency – cats.

- Panting. Iodine excess.

- Paralysis. Thiamine deficiency.

- Paraparesis. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Paw pad sloughing. Isoleucine deficiency – kittens.

- Periarticular exostoses. Vitamin A excess.

- Perioral lesions. Methionine and cystine deficiency – kittens.

- Photophobia. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Pica. Iron deficiency; phosphorus deficiency.

- Polydipsia. Vitamin D toxicity.

- Polyneuropathy. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Polyuria. Vitamin D toxicity.

- Porphyrin-like staining around the eyes, nose and mouth. Isoleucine deficiency – kittens.

- Poor pupillary light reflex. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Proprioceptive deficits. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Progressive retinal degeneration. Taurine deficiency – cats; vitamin A deficiency.

- Pulse bounding. Iron deficiency.

- Pupillary light reflex delayed. Vitamin A deficiency.

- Recumbency. Thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs.

- Renal tubular atrophy. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency – kittens.

- Reproductive problems. Isoleucine deficiency – cats; arachidonic acid deficiency – queens; vitamin A deficiency; vitamin E deficiency; taurine deficiency – cats.

- Restlessness. Calcium deficiency; iodine excess.

- Retinal degeneration (central). Taurine deficiency – cats; vitamin E deficiency – dogs.

- Salivary gland metaplasia. Vitamin A deficiency

- Salivation excess. Arginine deficiency – dogs; phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – kittens; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – dogs.

- Seizures/convulsions. Arginine deficiency – dogs; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; vitamin A deficiency; vitamin A excess; vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) deficiency – dogs.

- Shock. Iron excess.

- Skeletal abnormalities. Calcium deficiency; calcium excess; phosphorus deficiency; phosphorus excess; abnormal Ca:P ratio; vitamin E deficiency – dogs.

- Skin lesions. Zinc deficiency (face, head, paws) parakeratotic, hyperkeratosis.

- Skin scaling. Linoleic acid deficiency – puppies.

- Soft tissue calcification. Calcium excess; phosphorus excess; vitamin D toxicity.

- Spherocyte formation. Zinc toxicity.

- Sterility. Vitamin E deficiency – male dog.

- Stiffness. Calcium deficiency; vitamin D deficiency; vitamin D toxicity.

- Subcutaneous oedema: Vitamin E deficiency – dogs.

- Tachycardia. Iodine excess; iron excess; thiamine deficiency.

- Tail bent forwards. Phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – kittens.

- Testicular hypoplasia. Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency – dogs and cats.

- Tetanic spasms. Arginine deficiency – cats.

- Thrombocytopenia. Phosphorus deficiency – dogs.

- Thymus atrophy. Choline deficiency – puppies.

- Thyroxine low in blood. Vitamin A excess.

- Tremors. Threonine deficiency – kittens; magnesium deficiency – puppies and kittens.

- Vestibular signs. Thiamine deficiency – cats.

- Vocalisation. Phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – kittens.

- Vomiting. Arginine deficiency – cats and dogs; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; iron toxicity; zinc toxicity; thiamine deficiency – cats; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – dogs.

- Weight gain. Iodine deficiency.

- Weight loss. Isoleucine deficiency – kittens; leucine deficiency; lysine deficiency; lysine; methionine and cystine – puppies and kittens; phenylalanine and tyrosine deficiency – puppies; thiamine deficiency – cats and dogs; threonine deficiency – dogs and kittens; tryptophan deficiency – puppies and kittens; valine deficiency – puppies and kittens; iron deficiency; vitamin A deficiency; thiamine deficiency – cats; vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency – dogs; vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) deficiency – dogs and cats; vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency; vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency – cats; vitamin B7 (biotin) dogs and cats when given egg white containing avidin; vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency.

- Xerosis. Vitamin A deficiency.

Nutrition in the management of diseases

For animals with clinical disease, the following protocol should be adopted:

- Conduct a full physical examination to identify concurrent subclinical, as well as clinical conditions.

- Conduct a full nutritional history.

- Consider whether nutrition is a cause of the signs.

- Consider whether nutrition is a confounding problem in the animal.

- Consider the objectives of nutritional intervention:

- Meet energy requirements – these may be higher or lower than expected.

- Consider the best proportion of sources of energy for the animal – fat, protein, carbohydrates.

- Meet all essential nutritional requirements – which may be higher if the patient is unable to manufacture sufficient, or more if it is losing nutrients. Requirements may be lower if accumulation or toxicity is occurring.

- Avoid high intake of nutrients that might be detrimental; for example, fibres or phytate-containing plants that may reduce bioavailability, phosphates in chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- Ensure nutrients are properly balanced to each other; for example, Ca:P or Cu:Zn.

- Add in supplements that may be beneficial; for example, antioxidants such as vitamin E or omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid or docosahexaenoic acid for their anti-inflammatory effects.

- Add in novel ingredients that have evidence to show they may be beneficial; for example, L-carnitine or resistant-starch in the management of obesity.

Only use products that are safe in the intended species. Do not assume foodstuffs safe for humans are safe for dogs or cats. Only use products that have scientific evidence to demonstrate efficacy in the target species at the doses being advised. Too many nutritional products imply health benefits, but have little or no evidence to support their claims. Clinical signs associated with nutrient deficiency can occur within hours of a meal; for example, in cats, when dietary intake of arginine is insufficient, food ingestion is reduced, followed by hyperammonaemia, and seizures can occur within one to three hours after feeding due to impaired ureagenesis in the liver.

Nutritional errors (imbalances, excesses or deficiencies) as a cause of clinical disease are under diagnosed in veterinary practices for several reasons:

- Primary care clinicians generally have poor understanding about nutritional causes of clinical signs.

- Primary care clinicians rarely have sufficient time during a consultation to perform a detailed nutritional assessment.

- The information provided on pet food labels is insufficient to allow a detailed appraisal.

- If a nutritional problem is suspected, it is not easy to have pet foods analysed.

- It can be very expensive to have some nutrients quantified; for example, fatty acids and amino acids.

- Biomarkers are not always available to determine nutritional status.

- A false assumption exists that pet foods labelled complete are actually complete and balanced, when most are not.

- The cost of analysis and biomarkers can be high, and interpretation of results can be complex.

In the nutritional management of disease, it is imperative to choose a ration that is appropriate for the individual animal. A “one diet fits all” situation never exists.

Use diets that have been granted PARNUT status – that is, nutritional product for a particular nutritional purpose. These foods have been specially formulated to meet the requirements of animals with specific disorders, and that may require modifying the minimum amounts to be less than the usual FEDIAF guideline states.

These products must have evidence such as randomised controlled clinical trials to support their use; for example, low phosphorus diets for cats and dogs with chronic kidney disease, or less than the minimum requirement for iodine in prescription diets to control feline hyperthyroidism.

Conclusions

Nutritional deficiencies, excesses and imbalances are common causes of disease in cats and dogs.

Veterinary clinicians should obtain detailed nutritional history to rule in, or out, nutrition as a cause of clinical signs, before introducing medical interventions – particularly those that require long-term administration and have potential side effects.

Nutritional intervention may be all that is needed to manage many clinical diseases such as obesity in dogs and cats, or hyperthyroidism or type 2 non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in obese cats. The veterinary profession should only use products that are safe and have scientific evidence to demonstrate efficacy. Pet foods labelled as complete may not be, and may need to be analysed if nutritional errors are suspected.

Clients should be discouraged from feeding diets that have been shown to increase risks, including homemade recipes, raw meat diets and poorly formulated plant-based foods.

Unregulated addition of foods that can alter microbiome profile or reduce nutrient bioavailability should also be discouraged.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2026), Volume 56, Issue 01, Pages 6-13

-

Mike Davies qualified from the RVC, has RCVS postgraduate certificates in veterinary radiology and small animal orthopaedics, and holds a fellowship by examination in clinical nutrition in cats and dogs. He is an RCVS specialist in veterinary nutrition (small animal clinical nutrition). Mike has worked in academia and private practice, and for several pet food manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies. He speaks internationally on clinical nutrition and geriatrics, and founded the original City and Guilds certificate in small animal nutrition, and the BVNA certificates in small animal and exotic nutrition. He runs Provet’s certificate course in clinical nutrition.

More on nutrition in cats and dogs

References

- Abadie RB et al (2023). Vitamin A-mediated birth defects: a narrative review, Cureus 15(12): e50513.

- Abbrecht PH (1972). Cardiovascular effects of chronic potassium deficiency in the dog, Am J Physiol 223(3): 555-560.

- Albretsen J (2006). Toxicology brief: the toxicity of iron, an essential element, DVM360, tinyurl.com/6bcayywk

- Alexander J et al (2019). Effects of the long-term feeding of diets enriched with inorganic phosphorus on the adult feline kidney and phosphorus metabolism, Br J Nutr 121(3): 249-269.

- Amundson LA et al (2024). Copper metabolism and its implications for canine nutrition, Transl Anim Sci 8: txad147.

- Arvanitakis C (1978). Functional and morphological abnormalities of the small intestinal mucosa in pernicious anemia – a prospective study, Acta Hepatogastroenterol 25(4): 313-318.

- Axelrod AE et al (1940). The production of uncomplicated riboflavin deficiency in the dog, Am J Physiol 128: 703-708.

- Battersby IA et al (2005). Hyperammonaemic encephalopathy secondary to selective cobalamin deficiency in a juvenile Border collie, J Small Anim Pract 46(7): 339-344.

- Bauer A et al (2018). MKLN1 splicing defect in dogs with lethal acrodermatitis, Plos Genet 14(3): e1007264.

- Biourge V and Sergheraert R (2002). Hair pigmentation can be affected by diet in dogs, Proc Comp Nutr Soc 2002 4: 103-104.

- Bischoff K et al (2017). Zinc toxicosis in a boxer dog secondary to ingestion of holiday garland, J Med Toxicol 13(3): 263-266.

- Blundell R and Adam F (2013). Haemolytic anaemia and acute pancreatitis associated with zinc toxicosis in a dog, Vet Rec 172(1): 17.

- Brigelius-Flohé R and Traber MG (1999). Vitamin E: function and metabolism, FASEB J 13(10): 1,145-1,155.

- Burns RA and Milner JA (1981). Sulfur amino acid requirements of immature beagle dogs, J Nutr 111(12): 2,117-2,124

- Burns RA and Milner JA (1982). Threonine, tryptophan and histidine requirements of immature beagle dogs, J Nutr 112(3): 447-452.

- Burton AG and Hopper K (2019). Hyponatremia in dogs and cats, J Vet Emerg Crit Care 29(5): 461-471.

- Butterwick R et al (2015a). Branched-Chain Amino Acids - Nutrition, WikiVet, tinyurl.com/55ds3hbs

- Butterwick R et al (2015b). Chloride - Nutrition, WikiVet, tinyurl.com/mr54vd6m

- Butterwick R et al (2015c). Manganese - Nutrition, WikiVet, tinyurl.com/bnppbs4f

- Center SA et al (2021). Is it time to reconsider current guidelines for copper content in commercial dog foods?, J Am Vet Med Assoc 258(4):357-364.

- Che D et al (2021). Amino acids in the nutrition, metabolism, and health of domestic cats. In Wu G (eds), Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health, Cham, Springer: 217-231.

- Chow CK (2000). Vitamin E. In Stipanuk MH (ed), Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition, WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia: 584-598.

- Christian JS and Rege RV (1996). Methionine, but not taurine, protects against formation of canine pigmented gallstones, J Surg Res 61(1): 275-281.

- Cianciaruso B et al (1981). Histidine, an essential amino acid for adult dogs, J Nutr 111(6): 1,074-1,084.

- Clarke KE et al (2021). Vitamin D metabolism and disorders in dogs and cats, J Small Anim Pract 62(11): 935-947.

- Colombini S (1999). Canine zinc-responsive dermatosis, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 29(6): 1,373-1,383.

- Corbee RJM (2020). Vitamin D in health and disease in dogs and cats, Adv Small Anim Care 1(2): 265-277.

- Davidson MG et al (1998). Retinal degeneration associated with vitamin E deficiency in hunting dogs, J Am Vet Med Assoc 213(5): 645-651.

- Davies M (2014). Variability in content of homemade diets for canine chronic kidney disease, Vet Rec 174(14): 352.

- Davies M et al (2017). Mineral analysis of complete dog and cat foods in the UK and compliance with European guidelines, Sci Rep 7(1): 17107.

- De Fornel-Thibaud P et al (2007). Unusual case of osteopenia associated with nutritional calcium and vitamin D deficiency in an adult dog, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 43(1): 52-60.

- Dillitzer N et al (2011). Intake of minerals, trace elements and vitamins in bone and raw food rations in adult dogs, Br J Nutr 106(Suppl 1): S53-S56.

- Dobenecker B et al (2018). Effect of a high phosphorus diet on indicators of renal health in cats, J Feline Med Surg 20(4): 339-343.

- Dor C et al (2018). Acquired urea cycle amino acid deficiency and hyperammonaemic encephalopathy in a cat with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic kidney disease, JFMS Open Rep 4(2): 2055116918786750.

- Dow SW et al (1987). Potassium depletion in cats: renal and dietary influences, J Am Vet Med Assoc 191(12): 1,569-1,575.

- Dow SW et al (1990). Effects of dietary acidification and potassium depletion on acid base balance, mineral metabolism and renal function in adult cats, J Nutr 120(6): 569-578.

- Espadas I et al (2017). MRI, CT and histopathological findings in a cat with hypovitaminosis A, Vet Rec 5: e000467.

- Elvehjem CA et al (1944). The effect of vitamin E on reproduction of dogs on milk diets, J Pediatr 24(4): 436-441.

- FEDIAF (2025). FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines, tinyurl.com/4bmxt7sd

- Fordyce HH et al (2000). Persistent cobalamin deficiency causing failure to thrive in a juvenile beagle, J Small Anim Pract 41(9): 407-410.

- Freeman LM et al (2006). Effects of dietary modification in dogs with early chronic valvular disease, J Vet Intern Med 20(5): 1,116-1,126.

- Freeman LM et al (2018). Diet-associated dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs: what do we know?, J Am Vet Med Assoc 253(11): 1,390-1,394.

- Fuller TJ et al (1978). Reversible depression in myocardial performance in dogs with experimental phosphorus deficiency, J Clin Invest 62(6): 1,194-1,200.

- Gershoff SN and Gottlieb LS (1964). Pantothenic acid deficiency in cats, J Nutr 82(1): 135-138.

- Giger U (2005). Regenerative anemias caused by blood loss or hemolysis. In Ettinger SJ and Feldman EC (eds), Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (6th edn), Elsevier Saunders, St Louis: 1,886-1,908.

- Gold AJ et al (2015). Failure to thrive and life-threatening complications due to inherited selective cobalamin malabsorption effectively managed in a juvenile Australian Shepherd dog, Can Vet J 56(10): 1,029-1,034.

- Green HN and Mellanby E (1928). Vitamin A as an anti-infective agent Br Med J 2(3,537): 691.

- Greentree WF and Hall JO (1995). Iron toxicosis. In Bonagura JD (ed), Kirk’s Current Therapy XII: Small Animal Practice, WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia: 240-242.

- Guidi D et al (2022). Investigation on iodine levels in canine and feline canned food products in Italy, Progr Nutr 23(4): e2021151.

- Gurnee CM and Drobatz KJ (2007). Zinc intoxication in dogs: 19 cases (1991–2003), J Am Vet Med Assoc 230(8): 1,174-1,179.

- Ha YH et al (1978). Arginine requirements in immature dogs, J Nutr 108(2): 203-210.

- Hackel DB et al (1953). Effects of thiamin deficiency on myocardial metabolism in intact dogs, Am Heart J 46(6): 883-894.

- Hargrove DM et al (1984). Leucine and isoleucine requirements of the kitten, Br J Nutr 52(3): 595-605.

- Harvey JW (2008). Iron metabolism and its disorders. In Kaneko JJ et al (eds), Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals (6th edn), Elsevier, Burlington: 259-285.

- Houston DM and Hulland TJ (1988). Thiamine deficiency in a team of sled dogs, Can Vet J 29(4): 383-385.

- Ihrke PJ and Goldschmidt MH (1983). Vitamin A-responsive dermatosis in the dog, J Am Vet Med Assoc 182(7): 687-690.

- Kiani AK et al (2022). Main nutritional deficiencies, J Prev Med Hyg 63(2 Suppl 3): E93-E101.

- Kidder AC and Chew D (2009). Treatment options for hyperphosphatemia in feline CKD: what’s out there?, J Feline Med Surg 11(11): 913-924.

- Köhler B et al (2012). Dietary hyperthyroidism in dogs, J Small Anim Pract 53(3): 182-184.

- Kritikos G et al (2017). The role of thiamine and effects of deficiency in dogs and cats, Vet Sci 4(4):59.

- Larsen JA et al (2012). Evaluation of recipes for home-prepared diets for dogs and cats with chronic kidney disease, J Am Vet Med Assoc 240(5): 532-538.

- Lee FF et al (2016). Localized parakeratotic hyperkeratosis in sixteen Boston terrier dogs, Vet Dermatol 27(5): 384–e396.

- Leon A et al (1992). Hypokalaemic episodic polymyopathy in cats fed a vegetarian diet, Aust Vet J 69(10): 249-254.

- Li P and Wu G (2023). Amino acid nutrition and metabolism in domestic cats and dogs, J Anim Sci Biotechnol 14(1): 19.

- McCauley SR et al (2020). Review of canine dilated cardiomyopathy in the wake of diet-associated concerns, J Anim Sci 98(6): skaa155.

- MacDonald ML et al (1984). Effects of linoleate and arachidonate deficiency on reproduction and spermatogenesis in the cat, J Nutr 114(4): 719-726.

- McDowell LR (1989). Vitamins in Animal Nutrition, Academic Press, San Diego.

- McDowell LR (1992). Minerals in Animal and Human Nutrition, Academic Press, San Diego.

- McEwan NA et al (2000). Diagnostic features, confirmation and disease progression in 28 cases of lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers, J Small Anim Pract 41(11): 501-507.

- Markovich JE et al (2013). Thiamine deficiency in dogs and cats, J Am Vet Med Assoc 243(5): 649-656.

- Mellanby E (1926). Diet and disease, with special reference to the teeth, lungs, and pre-natal feeding, Lancet 1: 515-519.

- Mellanby RJ et al (2005). Hypercalcaemia in two dogs caused by excessive dietary supplementation of vitamin D, J Small Anim Pract 46(7): 334-338.

- Mellema MS and Hoareau GL (2014). Hypomagnesemia in brachycephalic dogs, J Vet Intern Med 28(5): 1,418-1,423.

- Milner JA (1979). Assessment of indispensable and dispensable amino acids for the immature dog, J Nutr 109(7): 1,161-1,167.

- Milner JA et al (1984). Phenylalanine and tyrosine requirement in immature beagle dogs, J Nutr 114(12): 2,212-2,216.

- Morris JG and Rogers QR (1978). Arginine: an essential amino acid for the cat, J Nutr 108(12): 1,944-1,953.

- Naigamwalla DZ et al (2012). Iron deficiency anemia, Can Vet J 53(3): 250-256.

- NRC (2006). Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

- Noel PR et al (1972). Riboflavin supplementation in the dog, Res Vet Sci 13(5): 443-450.

- Nuttall WO (1986). Iodine deficiency in working dogs, N Z Vet J 34(5): 72.

- Olcott HS (1933). Vitamin A deficiency in the dog, Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1933 30: 767.

- Pedrinelli V et al (2019). Concentrations of macronutrients, minerals and heavy metals in home-prepared diets for adult dogs and cats, Sci Rep 9(1): 13058.

- Peixoto PV et al (2012). Considerations about the levels of iodine in the diet and the occurrence of hypothyroidism in dogs and humans in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Brazil J Vet Med 34(3): 223-229.

- Pereira AM et al (2021). Zinc in dog nutrition, health and disease: a review, Animals 11(4): 978.

- Pion PD et al (1992). Response of cats with dilated cardiomyopathy to taurine supplementation, J Am Vet Med Assoc 201(2): 275-284.

- Provet (2013). Niacin, tinyurl.com/2a6nka4s

- Quam DD et al (1987). Histidine requirements for growing kittens for growth, haematopoesis and prevention of cataracts, Br J Nutr 58(3): 521-532.

- Ranz D et al (2002). Nutritional lens opacities in two litters of Newfoundland dogs, J Nutr 132(6 Suppl 2) 1688S–1689S.

- Read DH et al (1977). Polioencephalomalacia of dogs with thiamine deficiency, Vet Pathol 14(2): 103-112.

- Redzic S et al (2023). Niacin deficiency, StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island.

- Reed N et al (2007). Cobalamin, folate and inorganic phosphate abnormalities in ill cats, J Feline Med Surg 9(4): 278-288.

- Rivers JPW (1982). Essential fatty acids in cats, J Small Anim Pract 23(9): 563-576.

- Rogers QR and Morris JG (1979). Essentiality of amino acids for the growing kitten, J Nutr 109(4): 718-723.

- Ruegamer W et al (1946). Potassium deficiency in the dog, Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 61: 234-238.

- Ryu M-O et al (2024). Proximate analysis and profiles of amino acids, fatty acids, and minerals in insect-based foods for dogs, Am J Vet Res 86(1): ajvr.24.08.0243.

- Sahebari M et al (2019). Selenium and autoimmune diseases: a review article, Curr Rheumatol Rev 15(2): 123-134.

- Salvadori C et al (2003). Degenerative myelopathy associated with cobalamin deficiency in a cat, J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 50(6): 292-296.

- Schoenmakers I et al (1999). Excessive Ca and P intake during early maturation in dogs alters Ca and P balance without long-term effects after dietary normalization, J Nutr 129(5): 1,068-1,074.

- Schulz N et al (2018). Magnesium in dogs and cats - physiology, analysis, and magnesium disorders, Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere 46(1): 21-32.

- Scott PP et al (1964). Nutritional blindness in the cat, Exp Eye Res 3: 357–364.

- Shastak Y and Pelletier W (2024). Pet wellness and vitamin A: a narrative overview, Animals 14(7): 1,000.

- Sinclair AJ et al (1981). Essential fatty acid deficiency and evidence for arachidonate synthesis in the cat, Br J Nutr 46(1): 93-96.

- Singh M et al (2005). Thiamine deficiency in dogs due to the feeding of sulphite preserved meat, Aust Vet J 83(7): 412-417.

- Soltanian A et al (2016). Comparison of serum trace elements and antioxidant levels in terrier dogs with or without behavior problems, Appl Anim Behav Sci 180: 87-92.

- Spangler WL (1979). Pathophysiologic response of the juxtaglomerular apparatus to dietary sodium restriction in the dog, Am J Vet Res 40(6): 809-899.

- Stimson AM and Hedley OF (1933). Observations on vitamin A deficiency in dogs, Public Health Rep 48: 445-449.

- Street HR and Cowgill GR (1939). Acute riboflavin deficiency in the dog, Am J Physiol 125: 323-334.

- Sutherland KAK et al (2020). Lysine requirements in small, medium, and large breed adult dogs using the indicator amino acid oxidation technique, Transl Anim Sci 4(3): txaa082.

- Swank RL et al (1941). The production and study of cardiac failure in thiamin-deficient dogs, Am Heart J 22(2): 154-168.

- Teeter RG et al (1978). Essentiality of methionine in the cat, J Anim Sci 46(5): 1,287-1,292.

- Thornburg LP (2000). A perspective on copper and liver disease in the dog, J Vet Diagn Invest 12(2): 101-110.

- Titchenal CA et al (1980). Threonine imbalance, deficiency, and neurological dysfunction in the kitten, J Nutr 110(12): 2,444-2,459.

- Ueda Y et al (2015). Incidence, severity and prognosis associated with hyponatremia in dogs and cats, J Vet Intern Med 29(3): 794-800.

- Ullal TV et al (2023). Association of folate concentrations with clinical signs and laboratory markers of chronic enteropathy in dogs, J Vet Intern Med 37(2): 455-464.

- Van den Broek AHM and Thoday KL (1986). Skin disease in dogs associated with zinc deficiency: a report of five cases, J Small Anim Pract 27(5): 313-323.

- Van Vleet JF (1975). Experimentally induced vitamin E-selenium deficiency in the growing dog, J Am Vet Med Assoc 166(8): 769-774.

- Verstegen J et al (2008). Canine and feline pregnancy loss due to viral and non-infectious causes: a review, Theriogenology 70(3): 304-319.

- Wall T (2022). FDA ends DCM updates; No causality data with dog foods, Pet Food Industry, tinyurl.com/yckfvvn8

- Weise HF et al (1962). Influence of high and low caloric intakes on fat deficiency of dogs, J Nutr 76(1): 71-81.

- Weiss DJ (2010). Iron and copper deficiencies and disorders of iron metabolism. In Weiss DJ and Wardrop KJ (eds), Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology (6th edn), Blackwell Publishing, Ames: 167-171.

- White SD et al (2001). Zinc-responsive dermatosis in dogs: 41 cases and literature review, Vet Dermatol 12(2): 101-109.

- Yawata Y et al (1974). Blood cell abnormalities complicating the hypophosphatemia of hyperalimentation: erythrocyte and platelet ATP deficiency associated with haemolytic anemia and bleeding in the hyperalimented dog, J Lab Clin Med 84: 643-653.

- Yu SC et al (2001). Effect of low levels of dietary tyrosine on the hair colour of cats, J Small Anim Pract 42(4): 176-180.

- Zafalon RVA et al (2020). Nutritional inadequacies in commercial vegan foods for dogs and cats, Plos One 15(1): e0227046.

- Zentek J and Meyer H (1991). Investigations on copper deficiency in growing dogs, J Nutr 121(11 Suppl): S83-S84.